A vision of destruction restored: Using eyetracking to guide the restoration of John Martin’s “The Destruction of Pompeii and Herculaneum”

Submitting Institution

Birkbeck CollegeUnit of Assessment

Psychology, Psychiatry and NeuroscienceSummary Impact Type

CulturalResearch Subject Area(s)

Medical and Health Sciences: Neurosciences

Psychology and Cognitive Sciences: Psychology

Summary of the impact

John Martin's painting `Destruction of Pompeii and Herculaneum'

was damaged and considered lost until advances in conservation made a

restoration feasible. The question remained of how to fill the lost

section without generating attentional distraction. Together with TATE

Britain, Tim J. Smith used eyetracking to identify restoration procedures

that directed gaze towards the remaining content and allowed full

comprehension of the painting's subject matter. The restored painting is

now on permanent display at TATE. This study is the first to apply

eyetracking and vision science to art conservation, and has been received

with great interest by the international conservation community.

Underpinning research

Whether we appreciate a work of art or a computer screen, we utilise the

same sensory and cognitive apparatus. Understanding how visual mechanisms

construct our experience of a painting is important for understanding how

the composition of a painting can influence our experience. Until

recently, scientific understanding of visual cognition has rarely been

applied to visual art, and artists had to intuit viewer cognition through

introspection. The work of Tim J. Smith aims to apply contemporary

theories and methodologies from visual cognition to visual art and visual

media. His research uses eye tracking to record eye movements and to

determine how they are controlled both by a visual stimulus and by viewer

cognition. Due to the limitations of the eye, we are only able to perceive

detail in an area about 2 degrees around the centre of our gaze (where 360

degrees would encircle our head). We are unaware of the incomplete nature

of our visual experience, as eye movements quickly bring any relevant

object into this central region.

By recording eye movements and fixations, we can gain insights into what

viewers are most likely to perceive and remember of a scene. Smith's

research has shown that how long we fixate objects in a scene influences

whether we later remember them (Rayner, Smith, Malcolm, & Henderson,

2009), and that fixation durations are determined by the currently fixated

object and our previous fixations (Smith & Henderson, 2011). Smith has

shown that image features such as colour, luminance, clutter and motion

influence where we look (Henderson, Chanceaux, & Smith, 2009; Smith

& Mital, in press). Manipulation of these features can be used by

painters and film directors to guide attention (Smith, 2013). By using

computer vision techniques to identify salient features of an image that

might capture attention and computational modelling of attention and eye

movements (Nuthmann, Smith, Engbert, & Henderson, 2010), Smith's

research has provided detailed insight into the relationship between an

image and how it is cognitively processed by a viewer. Particularly

relevant for the work with TATE Britain is the fact that contours and

edges involuntarily attract eye movements, while regions with low spatial

frequency (i.e., uniform or blurred areas) tend to be avoided during

visual exploration.

The restoration of the John Martin painting (section 4) presented a novel

challenge for Smith. The loss of a large part of the painting's canvas

raised the question how to fill the lost section in a way that would not

distract from the existing content. The traditional approach initially

favoured by the TATE conservation team was to fill the loss with a neutral

colour, as proposed by Cesare Brandi ("Theory of Restoration", 1963) on

the basis of gestalt principles. Smith's research into how visual features

influence eye movements and attention suggested that such a neutral infill

would be detrimental and distract from the main content. His work with

TATE Britain employed a combination of eye tracking, computational

analysis of image features and gaze to determine the optimal method of

restoring Martin's painting.

References to the research

Smith, T. J. (2013) Watching you watch movies: Using eye tracking to

inform cognitive film theory. In A. P. Shimamura (Ed.), Psychocinematics:

Exploring Cognition at the Movies. New York: Oxford University

Press.

Smith, T. J., & Henderson, J. M. (2011) Looking back at Waldo:

oculomotor inhibition of return foes not prevent return fixations. Journal

of Vision, 11(1): 3, 1-11.

Nuthmann, A., Smith, T.J., Engbert, R., & Henderson, J.M. (2010).

CRISP: A computational model of fixation durations in scene viewing. Psychological

Review, 117, 382-405.

Henderson, J.M., Chanceaux, M., & Smith, T.J. (2009) The Influence of

clutter on real-world scene search: Evidence from search efficiency and

eye movements. Journal of Vision, 9(1):32, 1-8.

Rayner, K., Smith, T.J., Malcolm, G.L., & Henderson, J.M. (2009). Eye

movements and visual encoding during scene perception. Psychological

Science, 20, 6-10

Smith, T. J., & Mital, P. K. (2013). Attentional synchrony and the

influence of viewing task on gaze behaviour in static and dynamic scenes.

Journal of Vision, 13(8):16, 1-24.

Details of the impact

John Martin was a British artist whose epic painting, Destruction of

Pompeii and Herculaneum (1821) was a central work of his apocalyptic

sublime style, which has influenced popular representations of

catastrophes such as Lord Of The Rings and Hollywood disaster movies.

Ironically, the painting suffered its own catastrophe when it was

extensively damaged following the 1928 Thames flood, including the loss of

approximately one-fifth of the canvas (Figure 1, left).

Figure 1: Left = John Martin's The Destruction of Pompeii

and Herculaneum before treatment. Right = Tate conservator

hand-restoring the painting based on the life-sized digital composite

(displayed to the right). Photograph courtesy of Sunday Times (published

Sunday 4th September, 2011).

Figure 1: Left = John Martin's The Destruction of Pompeii

and Herculaneum before treatment. Right = Tate conservator

hand-restoring the painting based on the life-sized digital composite

(displayed to the right). Photograph courtesy of Sunday Times (published

Sunday 4th September, 2011).

The painting was considered lost until advances in conservation

techniques made a restoration feasible. However, the question of how to

fill the lost section without distracting from the remaining portion

remained. To answer this question, Dr. Smith was consulted. He worked with

the conservation department of TATE from October 2010 to September 2011.

Together with the lead conservator, Smith created a digital reconstruction

of the complete canvas by integrating a digitized version of a smaller

intact copy by the artist. Digital manipulation of the reconstructed

version created a "best guess" of what the full original might have looked

like. The lost section was digitally altered to create several alternative

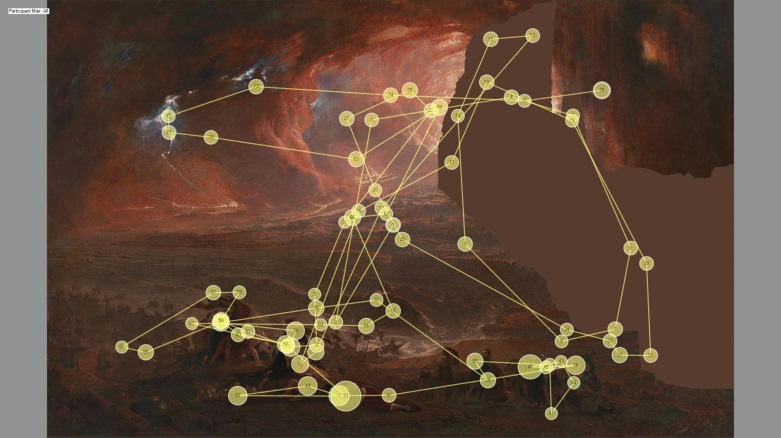

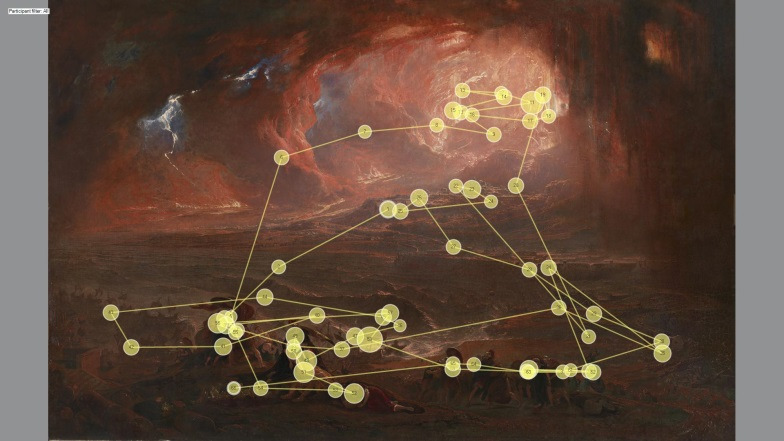

infill options, including a neutral colour infill (Figure 2, left), a

lower-contrast version, and an "abstracted" version with less edge

information. Computational saliency analysis by Smith predicted that

viewer attention would be undesirably attracted to the edge of the loss in

all versions, except for the full restoration and the "abstracted"

version. To validate these predictions, each version was presented to

twenty viewers. Eye movements were recorded using a Tobii TX300 head-free

eyetracker to approximate the conditions under which the painting would be

viewed in a gallery. Eyetracking illuminates which parts of the painting

attract attention (dots in Figure 2 indicate where the eyes stopped during

fixations), and how attention is shifted (Figure 2, lines). Analysis of

eye movements for the full digital restoration (Figure 2, right) revealed

that viewers spent most time fixating the mouth of the volcano and the

characters in the foreground. With the neutral colour infill (Figure 2,

left), the edges of the loss distracted from the original content, and

viewers failed to comprehend the subject matter of the painting when

quizzed afterwards. Prior to this eytracking evidence, TATE conservators

were considering the traditional technique of using a neutral infill to

replace the loss. Demonstrating the destructive impact this would have on

attention and comprehension led them to take the bolder step of a full

restoration with abstracted features in the restored section, to bias

attention towards the original content (Figure 1, right).

Figure 2: Gaze scanpaths for one participant viewing the Neutral

Infill restoration (left) and full restoration (right) of the painting.

Dots represent fixations; lines represent saccades.

Figure 2: Gaze scanpaths for one participant viewing the Neutral

Infill restoration (left) and full restoration (right) of the painting.

Dots represent fixations; lines represent saccades.

The restored painting went on display at TATE Britain as part of a John

Martin retrospective in September 2011. Critics of the painting

restoration plans were universally appreciative of the finished product: "Should

the canvas be made good and the missing portion left bare? ...Or should

a full restoration be attempted, with the missing portions repainted,

exactly as they were...? Happily, the Tate chose the latter."

(Waldemar Januszcak, Sunday Times, 2011). This view is mirrored by the

curator of the exhibition "The whole process behind making this

[restoration] decision was ... exemplary of how technical research,

experiment and curatorial and conservation can productively be brought

together.....A painting which has been in storage and neglected for over

80 years can be brought back to public view, and then not as a

`artefact' or technical curiosity, but as a powerful work of art.".

The painting has now been re-entered into the TATE catalogue and again

serves to illustrate John Martin's role in British art history. The

experimental and computational techniques used in this project have been

positively received by the painting conservation community at an

international conference (Maisey et al., 2011). This novel approach to

restoration has obvious potential for future application in a domain where

decisions are usually based on intuition rather than empirical fact.

According to TATE's lead curator "What would have been a curatorial

hunch was bolstered in very important ways by [the] empirical evidence."

For the lead conservator of the painting, the project with Smith "has

changed the way I work on a day to day basis" (sources 2 and 3 below).

Sources to corroborate the impact

(Full URLs and additional tinyurl links have been provided for all

weblinks. Copies of all source materials are available upon request if

external weblinks are no longer operational.)

- Maisey, S., Smithen, P., Vilaro-Soler, A., & Smith, T. J. (2011)

Recovering from destruction: the conservation, reintegration and

perceptual analysis of a flood-damaged painting by John Martin. International

Council of Museums: Committee for Conservation. Published Proceedings.

Lisbon, Portugal, September 19-23, 2011. PDF version of this article:http://www.bbk.ac.uk/psychology/our-staff/academic/tim-smith/documents/1320_459_MAISEY_paper_EN1.pdf/view

http://tinyurl.com/prba49e

- Lead conservator on Martin painting whilst at TATE Britain. Contact

details are provided separately. A copy of a letter from the conservator

describing the restoration project and the importance of using eye

tracking measures is available upon request.

- Lead Curator pre-1800 British Art, Tate. Curator on John Martin,

Apocalypse exhibition September 2011 - January 2012. Contact details are

provided separately. A copy of a letter from the lead curator describing

the restoration project and Smith's central role in this project is

available upon request.

- Guardian Online, article on restoration. Monday 19th

September, 2011

http://www.guardian.co.uk/artanddesign/2011/sep/19/john-martin-pompeii-painting-restored

http://tinyurl.com/5wkdjyy

- Guardian Online, Science Blog. Article by Dr Tim J. Smith on

experiment and painting restoration. Monday 3rd October,

2011.

http://www.guardian.co.uk/science/blog/2011/oct/03/vision-science-john-martin-destruction

http://tinyurl.com/owuqhu5

- BBC Breakfast, BBC1. Report on Smith's experiment at TATE and painting

restoration. Broadcast 25th October, 2011.

- Channel 4 News, Channel 4. Report on Smith's experiment at TATE/

Broadcast 19th September, 2011.

- Sunday Times, Culture magazine. Sunday 4th September, 2011.

http://www.thesundaytimes.co.uk/sto/Magazine/Features/article762110.ece

http://tinyurl.com/ou5o6ay