Understanding and addressing ethnic inequalities in mental health

Submitting Institution

Queen Mary, University of LondonUnit of Assessment

Public Health, Health Services and Primary CareSummary Impact Type

SocietalResearch Subject Area(s)

Medical and Health Sciences: Public Health and Health Services

Summary of the impact

Research by Bhui 1996-2013 showed striking differences by ethnic group in diagnosis and

management of mental health disorders due to a complex interplay of socio-cultural factors and

different perspectives of patients and professionals. Impacts included: [a] the development and

implementation of a UK-wide mental health policy 'Delivering Race Equality'; [b] a national training

and workforce development programme that shifted the conceptual paradigm from the cultural

competencies of individuals to system-wide intervention (called `cultural consultation'); [c] service

development research `Enhancing Pathways into Care' (EPIC) to implement findings and draw

lessons across four NHS Trusts; [d] incorporation of research findings into national and

international guidelines, and influence on mental health legislation and policy; and [e] a new phase

of research on implementing findings.

Underpinning research

Common mental disorders affect one in six adults in UK and cause significant morbidity. Psychotic

disorders affect one in 100 but are more disabling and have greater risk of disability, social

exclusion, self-harm, suicide and contact with specialist psychiatric services. Diagnosis and

management of mental health conditions vary by ethnicity. Since the mid-1990s Professor

Kamaldeep Bhui's team have conducted research at Queen Mary on cross-cultural psychiatry

aiming to identify and explore these ethnic differences and ensure that patients receive best care

and achieve optimum outcome whatever their ethnic group, social class, language, culture or

religion. The research can be divided into four broad groups:

2a: Descriptive epidemiology (research conducted 1996-98). Prof Bhui showed that Black

Caribbean people were more likely than Whites to enter care through forensic and psychiatric

routes, more likely to be detained under the Mental Health Act, and more likely to be diverted to

hospital from prisons, suggesting that their illness was less likely to be noticed by police or courts

[1]. His team also showed that South Asians are less likely to be referred to specialist psychiatric

care, despite seeing their GPs more often than other ethnic groups for all health problems [2].

These findings were partly, but not fully, explained by differing expressions of distress as well as

different thresholds (irrespective of GP ethnicity) for recognition of common mental disorders [2].

2b: Systematic review of compulsory detention (2001-02). A systematic review of 38 papers

and meta-analysis of 13 suitable studies quantified the excess detentions (odds ratio for being

compulsorily detained under mental health legislation if Black vs White = 4.3) [3].

2c: Quantitative surveys of socio-cultural determinants of mental health inequalities (2001-

08). Bhui et al undertook a series of surveys of discrimination / work stress and common mental

disorders, of which one secondary analysis showed that discrimination was an important risk factor

for common mental disorders [4]. Other studies implicated explanatory models and coping; and

socio-economic risk factors of common mental disorders [4]. This involved developing and

validating new survey instruments (eg the Barts Explanatory Model Interview) [5].

2d. Analysis of national suicide statistics by ethnic group (2006-07). Bhui led a national

evaluation of suicide and ethnicity [6] that documented a highly significant excess of suicide in

young (13-24 year old) black Caribbean and African men compared to white British men of the

same age. These findings were evident in both community and inpatient settings. The team also

showed that, in contrast to previous studies, South Asian women did not have significantly higher

rates of suicide. In a report to the Department of Health, the team demonstrated a near-absence of

community-based suicide prevention initiatives, and notably none aimed at high-risk Black men.

Queen Mary researchers included Professors Bhui, Stansfeld, Priebe, and Feder and Hull.

References to the research

Six papers listed of 40 relevant from this group (Queen Mary researchers in bold):

1. Bhui K, Brown P, Hardie T, Watson JP, Parrott J. African-Caribbean men remanded to Brixton

Prison. Psychiatric and forensic characteristics and outcome of final court appearance. British

Journal of Psychiatry 1998; 172: 337-44.

2. Bhui K, Bhugra D, Goldberg D, Dunn G, Desai M. Cultural influences on the prevalence of

common mental disorder, general practitioners' assessments and help-seeking among Punjabi

and English people visiting their general practitioner. Psychological Medicine 2001; 31: 815-25.

3. Bhui K, Stansfeld S, Hull S, Priebe S, Mole F, Feder G. Ethnic variations in pathways to and

use of specialist mental health services in the UK. Systematic review. British Journal of

Psychiatry 2003; 182: 105-16.

4. Bhui K, Stansfeld S, McKenzie K, Karlsen S, Nazroo J, Weich S. Racial/ethnic discrimination

and common mental disorders among workers: findings from the EMPIRIC Study of Ethnic

Minority Groups in the United Kingdom. American Journal of Public Health. 2005; 95: 496-501.

5. Bhui K, Rüdell K, Priebe S. Assessing explanatory models for common mental disorders.

Journal of Clinical Psychiatry 2006 67: 964-71.

6. Bhui K, McKenzie K. Rates and risk factors by ethnic group for suicides within a year of

contact with mental health services in England and Wales. Psychiatric Services 2008;59:414-6.

Details of the impact

4a. Informing public and professional debate on a sensitive issue

The findings emerged in the context of some high-profile deaths of Black men in UK psychiatric

hospitals, and raised awareness of ethnic inequalities in mental health. Prior to this research, the

prevailing paradigm for explaining these inequalities was `racism'. Not only was this an inaccurate

interpretation of the evidence; it also diverted policy attention into simplistic solutions (eg tick-lists

of `cultural competencies' in which staff would need to be trained), and to undermine efforts of NHS

organisations and staff to provide effective and personalized care taking account of culture.

Research in Queen Mary has steadily shifted this paradigm towards more nuanced and socio-

culturally informed perspectives. For example, the excess of compulsory detentions of Black men

for psychosis may be due in small part to `racism' or `cultural stereotyping', but a full explanation

must include other interacting variables, including poverty; educational background; stress and

discrimination in the workplace; cross-cultural differences in expressions of distress; differences in

family support and help-seeking behaviour; and medication adherence. The findings of this

research and evaluation of the national programme [7] led to the recognition among policymakers

that solutions must go beyond a behaviourist emphasis on `racial awareness' to embrace

organisational and systemic changes as well as personal culture and poor cultures of care.

4b. Informing and developing national legislation and policy (includes):

- Revisions to the Mental Health Bill 2006. This research was reviewed and evidence taken

when the new bill was being developed. The findings, cited in the consultation documents [8],

helped halt legislation that was feared to risk greater ethnic inequalities in use of the Mental

Health Act. The final Bill was modified in a way that was unlikely to further increase inequalities

in detention, and further research is investigating what explains increasing levels of compulsory

detention in hospital in all groups, and the persistent excess among black patients.

- Prof Bhui was invited to draft national policy in 1999-2004; this work produced a 5 year plan

(`Delivering Race Equality 2005-2010' [9]) incorporating new service models, training and

further research. Many impacts resulted from this policy in 2008-13. In many localities,

communities had a greater say in local services and were more engaged with NHS services by

informing the implementation of the Race Relations Amendment Act and by promoting more

sophisticated models of workforce development to meet the needs of culturally diverse

populations. Most importantly, every trust was charged with improving their delivery of care to

minority ethnic groups and to show this in inspections to the Regulator. Other impacts include:

- Prof Bhui co-authored a report to the Department of Health on suicides in Black and Minority

Ethnic (BME) groups [10], contributing to the emphasis in the newly launched (Sept 2012)

National Suicide Prevention Strategy and to the work of the 2006 strategy as part of the

`Delivering Race Equality' programme.

- A national Race Equality & Cultural Competence programme (RECC) was mandated for all

mental health professionals, driven by strategic health authorities (SHAs) [11]. It led to

inclusion of training by the Care Quality Commission in a race impact assessments of SHAs.

-

Five hundred `race equality leads', a new workforce, were introduced nationally requiring

each Strategic Health Authority to develop an action plan [12].

- As part of developing a competent and informed workforce to reduce inequalities, with pump-

priming funds from Department of Health, Bhui set up an MSc in 2002 (plus Certificate and

Diploma) in Transcultural Mental Health, delivered in an innovative online format to 80

students annually, now drawn from over 38 countries. This course has recently been extended

with new pathways in Psychological Therapies, and Mental Health & Law [13].

4c. Informing and developing national and international guidelines

This work has been cited by, and strongly influenced, guidelines by the National Institute of Health

and Clinical Excellence on schizophrenia, for which Bhui chaired the access and engagement

panel [14]; the World Psychiatric Association Guidelines on Mental Health of Migrants [15];

European Union Guidelines on Healthcare of migrants: EU-COST action [16]; and European

Psychiatric Association guidelines on Public Mental Health [17].

4d: Implementing and evaluating new care pathways in the NHS

The action research project led by Queen Mary (2005-2007) `Enhancing Pathways Into Care'

(EPIC) in four NHS trusts illustrated a range of ways of changing pathways into care and engaging

hard-to-reach groups to improve access, often through partnerships between voluntary and

statutory sector agencies [18]. For example, a Pakistani Muslim Centre developed a joint

assessment protocol with an early intervention team in order to improve access to psychiatric care

for women from this otherwise isolated population. In one site (Sheffield) local audits showed a

small reduction in the average duration of admissions among Black people. The evaluation showed

clinical leadership, transformational leadership and cultural confidence were key ingredients to the

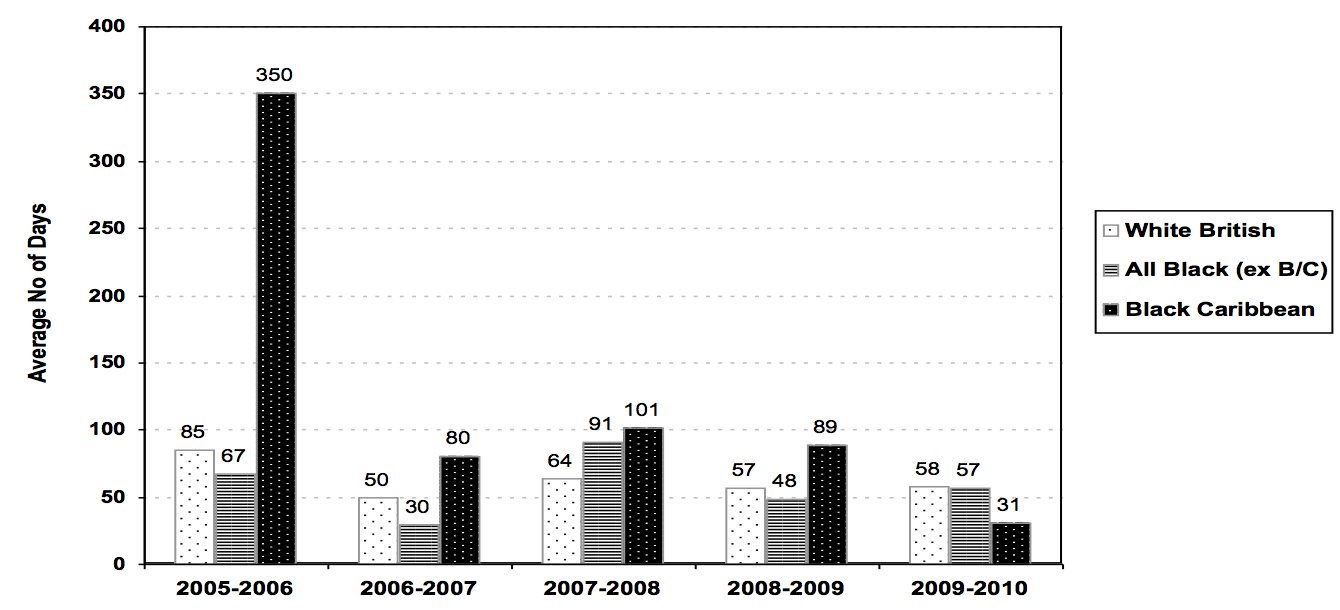

genuine change in services. The graph below (from a peer-reviewed publication in Transcultural

Psychiatry) shows one example of reduction in average length of stay in Black patients on

admissions on wards in Sheffield in a participating unit in the EPIC project in 2005-7.

4e: Informing and influencing training and workforce development

The Queen Mary team were commissioned by NHS Tower Hamlets (£450K) to provide the

Cultural Consultation Service to address intersectional inequalities arising in clinical practice.

Bhui set this up to provide individual staff training in holistic, socio-culturally informed care as well

as organisational and system-level support and guidance to NHS organisations seeking to reduce

inequalities in mental health service provision [19]. This is built on anthropological understandings

of culture, which notes the significance of beliefs, arts, laws, morals and behaviours found in all

ethnic groups. The model uses patient and staff narratives of care as the basis for intervention

alongside ethnographic research methods for evaluation. The team imported and adapted a

Canadian model to provide a new service, including in-service workforce development by teaching

staff how to use a cultural formulation, and addressing commissioning, management and team

influences. This and the narrative approach permitted more negotiated care plans for patients who

were disengaging or stuck in assertive outreach or other specialist psychiatric teams. The service

also included organizational analyses to assist the services and teams to adapt their ways of

working to reduce inequalities. Bhui led an audit of this service showing over 900 contacts, and

that cultural competency of staff improved [20]. Among a small sample of complex patients (n=36)

needing specialist and in-depth work, there were significant cost savings (£18K total) at three

month follow up. Patient functioning improved and trends showed fewer unmet needs.

4f: Informing further research

The overall picture nationally from the Care Quality Commission is that despite an evidence-based

intervention based on this research, there has been no overall reduction in ethnic inequalities in

detentions, ie that dramatic improvements in some areas (see graph above) are counterbalanced

by worsening inequalities in other areas. This has prompted new collaborative NIHR-funded

research studies to explore variations in compulsory admissions across the country [21].

Hypotheses include various geographical factors and social determinants of health.

4g: Oral and written evidence to Home Office and Government: Bhui's team undertook

research on Khat (widely used in some minority ethnic groups and linked to mental health

problems) and presented the case for it being made illegal [22].

Sources to corroborate the impact

- National Institute of Mental Health England 2003: `Inside Outside: Improving Mental Health

Services for BME Communities in England' (includes 27 references to Queen Mary research)

Inside Outside: Improving mental health services for BME communities in England.

- Mental Health Bill 2006. Hansard record of Queen Mary research being discussed in House of

Lords debate on this Bill: www.theyworkforyou.com/lords/?id=2006-11-

28c.679.2&s=Bhui#g704.0

- Department of Health and National Mental Health Development Unit. `Delivering Race Equality

in Mental Health Care: A Review' 2009 (www.nmhdu.org.uk/silo/files/delivering-race-equality-

in-mental-health-care-a-review.pdf, see page 11) includes EPIC evaluation lead by Bhui:

www.wolfson.qmul.ac.uk/psychiatry/epic

- National Mental Health Development Unit: `Suicide Prevention for BME Groups in England'

2006: www.nmhdu.org.uk/silo/files/suicide-prevention-for-bme-groups-in-england.pdf

- Race Equality and Cultural Competence programme (RECC), see `Delivering Race Equality in

Mental Health Care: A Review' 2009: www.nmhdu.org.uk/silo/files/delivering-race-equality-in-

mental-health-care-a-review.pdf

- Ministerial statement announcing 500 community development workers as race equality leads:

www.publications.parliament.uk/pa/cm200405/cmhansrd/vo050111/wmstext/50111m01.htm

- Training courses: www.wolfson.qmul.ac.uk/psychiatry/courses/ and

www.qmul.ac.uk/events/items/2012/83195.html

- NICE Guideline on Schizophrenia (updated 2010) www.nice.org.uk/CG82 See pages 9,10,11

and 30. Bhui et al, 2007 cited here has been accessed 28,648 times.

- World Psychiatric Association guidance on caring for migrants with mental health needs.

Bhugra, Gupta, Bhui et al, World Psychiatry 2011 10: 2-10.

www.wpanet.org/detail.php?section_id=7&content_id=895

- European Union Guidelines on Healthcare of migrants: EU-COST action:

www.cost.eu/domains_actions/isch/Actions/IS0603?management

- Campion J, Bhui K, Bhugra D. European Psychiatric Association (EPA) guidance on

prevention of mental disorders. European Psychiatry 2012; 27: 68-80.

- Reports on EPIC project. All papers listed here:

www.wolfson.qmul.ac.uk/psychiatry/epic/epicppublications.html, published in: International

Review of Psychiatry 2009; 21: 425-6, 450-9, 460-4, 465-471, 482-5. By Bhui, Moffatt,

McKenzie, Sass: www.wolfson.qmul.ac.uk/psychiatry/epic/epicevaluation.html

- Cultural Consultation website www.culturalconsultation.org

- Audit of Cultural Consultation Service. http://www.culturalconsultation.org.uk/wp-

content/uploads/2013/10/CCS-Final-report.pdf [available in archive]

- www.netscc.ac.uk/hsdr/projdetails.php?ref=10-1011-70

- Advisory Committee on Drug Misuse: Khat: A review of its potential harms to the individual and

communities in the UK. www.homeoffice.gov.uk/publications/agencies-public-

bodies/acmd1/ACMD-khat-report-2013/report-2013?view=Binary