NICE work: improving evidence-based clinical guideline development and implementation

Submitting Institution

Newcastle UniversityUnit of Assessment

Public Health, Health Services and Primary CareSummary Impact Type

EconomicResearch Subject Area(s)

Medical and Health Sciences: Public Health and Health Services

Summary of the impact

Clinical practice guidelines published in the UK by the National

Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) are constructed

using an approach based on methodological research led by Professor Martin

Eccles of Newcastle University. This systematic approach includes the

incorporation of health economics considerations and review after three

years (and if found necessary, an update of the guidelines); both

important outcomes of Newcastle research. The implementation of guidelines

has long been an area of concern. Professor Eccles established and chaired

(2008-12) the NICE Implementation Strategy Group, which sought to improve

the assistance that NICE gives organisations in order to aid the

implementation of guideline recommendations. Valid clinical practice

guidelines, when implemented, lead to health gains and predictable care

costs, thus helping both patients and the NHS.

Underpinning research

Key Researcher

Professor Martin Eccles conceived and led the research in Newcastle and

contributed significantly to collaborative work, detailed where

appropriate.

Background / context

Clinical practice guidelines, defined as "systematically developed

statements to assist practitioner and patient decisions about

appropriate health care for specific clinical circumstances",

represent one of the foundations for efforts to improve healthcare (Field

& Lohr, National Academy Press 1990). The development of clinical

practice guidelines (hereafter referred to as guidelines) began in the USA

in the early 1990s. However, legal challenges (a result of the largely

private nature of US healthcare) stopped progress soon afterwards leaving

significant methodological issues to be addressed, particularly

validation. Guidelines are considered valid only if: "when followed,

they lead to the health gains and costs predicted for them" (Field

& Lohr, National Academy Press 1992). When appropriately disseminated

and implemented, valid guidelines can lead to changes in clinical practice

and improvements in patient outcome. Conversely, the dissemination and

implementation of invalid guidelines may lead to wasteful use of resources

on ineffective interventions or, worse still, deterioration in patients'

health. Research at Newcastle University sought to fill this gap in the

development of valid guidelines.

Research

The research undertaken at Newcastle first addressed the question of how

best to develop valid guidelines that help to improve the quality of

patient care. Building on the general method developed by the Agency for

Health Care Policy and Research in the USA, and refining it for

application to the NHS, in 1996 Professor Eccles led the development of

the first evidence-based guideline in the UK (R1). The following year,

further guidelines were published, along with a practical methodology for

the production of evidence-based guidelines (R2).

There had been little theoretical exploration, and a lack of a widely

accepted means, of incorporating economic considerations into guidelines.

The NHS Research and Development Health Technology Assessment Programme

document How to develop cost conscious guidelines (R3), authored

jointly by Eccles and Mason (York University) in 2001, was the first

published practical approach in which cost and cost-effectiveness concepts

were successfully incorporated into guideline development processes.

Between 2001 and 2005, Newcastle researchers played a leading role in an

international research effort that studied guidelines in use. This showed

that guidelines have an average lifespan of about six years and stated "As

a general rule, guidelines should be reassessed for validity every 3

years." (R4, p1461) Further research led to a publication that

described approaches for updating clinical guidelines (R5).

In addition to this focus on guideline development, Newcastle researchers

developed an understanding of how new knowledge described in academic

medical literature was taken up by practising clinicians. This research

had implications for improving the implementation of guidelines in the

clinical setting (R6).

References to the research

(Newcastle author in bold type, citation counts from Scopus, July 2013)

R1. Eccles MP and members of the guideline development and

technical advisory groups. North of England evidence based guidelines

development project: summary version of evidence based guideline for the

primary care management of asthma in adults. British Medical Journal

1996;312:762-6. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/bmj.312.7033.762

Cited by 43.

R2. Eccles MP, Clapp Z, Grimshaw JM, Adams PC, Higgins B, Purves

I, Russell IT. North of England evidence based guideline development

project: methods of guideline development. British Medical Journal

1996;312:760-2. doi:

http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/bmj.312.7033.760 Cited by 140.

R3. Eccles M, Mason J. How to develop cost-conscious guidelines. Health

Technology Assessment 2001;5(16). doi:10.3310/hta5160 Cited by

96.

R4. Shekelle P, Ortiz E, Rhodes S, Morton S, Eccles M,

Grimshaw J, Woolf S. Validity of the agency for healthcare research and

quality clinical practice guidelines: how quickly do guidelines become

outdated? Journal of the American Medical Association

2001;286:1461-7. doi: 10.1001/jama.286.12.1461 Cited by 238.

(Eccles contributed to the study concept and design, the analysis of data,

and the critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual

content.)

R5. Eccles M, Rousseau N, Freemantle N. Updating evidence-based

clinical guidelines. Journal of Health Services Research and Policy

2002;7:98-103. doi:10.1258/1355819021927746 Cited by 15.

R6. Eccles M, Grimshaw J, Walker A, Johnson M, Pitts N. Changing

the behavior of healthcare professionals: the use of theory in promoting

the uptake of research findings. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology

2005;58:107-12. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2004.09.002 Cited by 213.

Relevant funding awards, by funder

Northern Regional Health Authority: Guidelines for management of

ischemic heart disease and asthma. 1993 for 18 months; £51,000.

NHS R&D Programme: Evaluating methods to promote the

implementation of research findings. 1997 for 42 months; £798,682.

Details of the impact

As a result of research led by Newcastle University, the UK National

Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) has adopted: (i)

methods by which the world's leading valid clinical practice guidelines

are produced; and (ii) processes that offer the best opportunity for

implementation by those responsible. This maximises the opportunities for

health gains for patients and predictable costs for the NHS.

The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence

NICE was established in 1999, and over time it has expanded its remit to

provide guidance and advice to improve health and social care. NICE

guidance supports healthcare professionals and others in England to ensure

that the care they provide is of the highest quality, and that it offers

the best value for money. NICE is internationally recognised for the way

in which recommendations are developed, using the best available evidence

(Ev a).

NICE guidelines: the ongoing impact of Newcastle research

The first guideline adopted by NICE was one developed by Eccles' research

group concerning secondary prophylaxis following myocardial infarction (Ev

b). NICE also adopted the approach by which the guideline (and those on

asthma (R1) and another on angina) was produced. Six research publications

(led by the Newcastle group) on guideline development (including R3, R5

and R6 above) were later cited in the first edition of the NICE

Guideline Development Manual (2004). These publications continue to

underpin the method for preparing guidelines, as can be observed most

recently in the November 2012 edition of the NICE Guideline

Development Manual (Ev c).

A total of 174 NICE guidelines had been produced using the approved

methods as of July 2013, the majority of which were after 2007. In the

seven years 2001-7, a total of 65 guidelines were published. In the

following five years 109 guidelines were published (Ev d). Of all

guidelines produced, 169 remain in force: 142 of which are in their

original form and 27 have been updated.

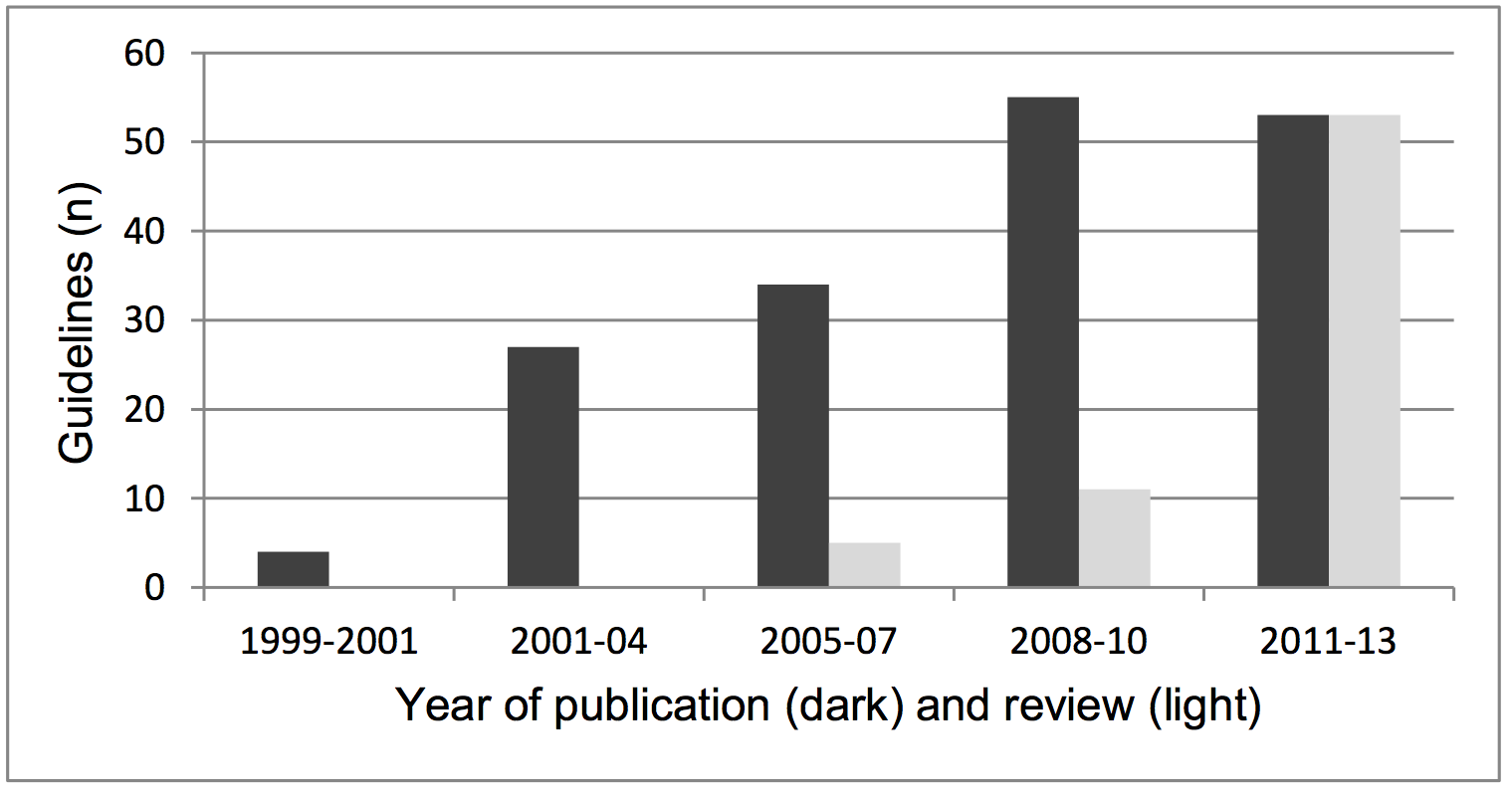

A significant development has been the introduction of the requirement to

review guidelines and, if necessary, update them. This process has largely

taken place since 2008 (see Figure 1). NICE policy, which is based on

Newcastle-led work on the lifespan of guidelines, is: "A formal review

of the need to update a guideline is usually undertaken by NICE 3 years

after its publication" (Ev c, p189). This three-year recommendation

is based on advice presented in the 2001 Journal of the American

Medical Association paper (R4). Since 2008, 22 guidelines have been

re-written, and 67 other guidelines have been subjected to the review

process. Five guidelines have been withdrawn as a result of the review

process.

Figure 1. The number of NICE guidelines (n) published and reviewed, by three-year periods.

(Data obtained from www.nice.org.uk/guidance, Ev d)

Figure 1. The number of NICE guidelines (n) published and reviewed, by three-year periods.

(Data obtained from www.nice.org.uk/guidance, Ev d)

Advising on development and implementation

The Deputy Chief Executive of NICE has said of Professor Eccles and his

research that:

"...your work on the effectiveness of strategies to implement evidence

based guidelines [... has] informed NICE's understanding of the

evidence base for implementation and led to the decision to form NICE's

Implementation Strategy Group." (Ev e)

Eccles chaired the Implementation Strategy Group from 2008 until retiring

from it in 2012 (Ev f). Consequently, Newcastle-led research on strategies

for promoting the uptake of research findings was incorporated into the

processes and activities of NICE.

Examples:

(i) Encouraging engagement in promoting implementation. Guidelines

are, and have always been, written and reviewed by external committees

convened for that purpose, rather than NICE staff. The Implementation

Strategy Group scrutinised the processes by which guideline development

committee members were recruited. As a result of Newcastle-led research on

behaviour change amongst professionals (R6), a recommendation was made

regarding the importance of appointing the appropriate people to promote

guideline implementation. As a result, since Autumn 2009, the NICE

Implementation Team has advised management on potential gaps in guideline

development committee membership in order to encourage the recruitment of

individuals who could be expected to champion the implementation of a

guideline.

(ii) Web-based practical advice on implementation. In 2009, the

Implementation Strategy Group gave advice (based on research such as that

described in R6) on promoting engagement with primary care services and

supported the production of web pages designed to aid general

practitioners with the implementation of guidelines. The Implementation

Programme Director of NICE has said:

"This is still a well used part of the site. ... A cross Institute

group on general practice was formed and still active in 2013. [The

number of page] views within the first weeks of its launch were

equivalent to that of our most viewed guideline which is unusually high

for a support product, rather than a guidance product." (Ev g)

Sources to corroborate the impact

Ev a. NICE website http://www.nice.org.uk/aboutnice/howwework/how_we_work.jsp

Ev b. The first NICE guideline can be found at: http://guidance.nice.org.uk/A

Ev c. NICE, `The guidelines manual' Published on 30

November 2012. The web version is available at http://publications.nice.org.uk/pmg6

and a searchable pdf version (downloaded 17/06/13) is available on

request.

Ev d. The individual guidelines are available, beginning at http://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/index.jsp?action=byType&type=2&status=3

and continuing for several pages. Dates were gathered from webpages and

tabulated. This data can be made available on request.

Ev e. A letter from the Deputy Chief Executive of NICE (who has

agreed to be contacted to corroborate these claims if required) is

available on request.

Ev f. Notification of the vacancy, with a description of the role

of the Implementation Strategy Group is available at

http://www.nice.org.uk/getinvolved/joinnwc/ChairAndMemberImplementationStrategyGroup.jsp

Ev g. A copy of e-mail communication with the Implementation

Programme Director of NICE (who has agreed to be contacted if required to

corroborate the claimed impacts) is available.