UOA05-01: A novel vaccination strategy to safeguard the Ethiopian wolf from extinction

Submitting Institution

University of OxfordUnit of Assessment

Biological SciencesSummary Impact Type

EnvironmentalResearch Subject Area(s)

Agricultural and Veterinary Sciences: Veterinary Sciences

Medical and Health Sciences: Clinical Sciences

Summary of the impact

The Ethiopian wolf is the most endangered carnivore in Africa. It is

chiefly threatened by rabies outbreaks that occur every 5-10 years with a

mortality rate of up to 77% in affected populations. Dr Claudio

Sillero-Zubiri and colleagues have developed a novel low-coverage

vaccination strategy, now at the heart of a strategic plan to protect this

species from extinction. Containment of rabies through a cordon

sanitaire protects these rare wolves beyond the initial outbreak,

offering a potential model for wildlife disease management elsewhere, and

significant socio-economic and health benefits for the communities living

in and around wolf areas.

Underpinning research

Fewer than 500 Ethiopian wolves survive in six small, isolated, mountain

pockets across Ethiopia, over half in the Bale Mountains. Expanding

agriculture and grazing in the Afroalpine region in which the wolves live

brings them into closer contact with domestic dogs, the main reservoir of

rabies. The risk posed by rabies is amplified by the wolves' social habits

and high density; their small population size makes them vulnerable to

extinction. Researchers at the Wildlife Conservation Research Unit

(WildCRU) at Oxford University's Zoology Department, led by Dr Claudio

Sillero-Zubiri and Professor David Macdonald, have carried out long-term

studies to identify the major threats faced by the wolves, and to

establish the most effective ways to ensure their continued survival.

As part of these long-term studies, Sillero-Zubiri observed that over a

4-month period in the early 1990s, 77% of the largest wolf population in

the Bale Mountains died or disappeared. Rabies (a major threat to wild

canids, and widespread amongst domestic dogs in Ethiopia) was the

suspected cause, and a virus type consistent with dog-associated rabies

was isolated from wolf carcasses. The results of all this research,

published in 1996, provided clear evidence that rabies outbreaks linked to

local domestic dogs were the main threat to the survival of wolves1.

Further research suggested that canine distemper virus might also affect

wolves, and reinforced the need to protect the wolves against diseases

carried by local dogs, of which there are very large numbers2.

Owing to their fragmented distribution, Ethiopian wolves effectively live

on islands in a sea of dogs.

A breakthrough as to how this protection might be achieved was provided

in a paper published in 2002. Sillero-Zubiri and colleagues used

Population Viability Analysis (PVA) modelling to quantify the impact of

rabies outbreaks on wolf populations. Modelling showed that, in the

absence of disease, populations were remarkably stable, but that rabies

epizootics caused extinction probabilities to rise substantially,

particularly in smaller populations. Importantly, the model suggested that

direct vaccination of as few as 20-40% of wolves against rabies might be

sufficient protection from the largest epizootics3. By averting

low population densities, and pack extinctions, this approach would

ameliorate delayed population recovery exacerbated by social constraints

on independent breeding4. This was a new approach to

vaccination: rather than attempting to eliminate the disease altogether

(often impractical in wild populations), targeted vaccination could

curtail the largest and most damaging outbreaks, reducing extinction risk.

Another major rabies outbreak in 2003-04 gave the team an opportunity to

test their vaccination strategy in practice. More than three-quarters

(76%) of wolves in the Web Valley of the Bale Mountains died over a period

of less than 6 months. Just under 40% of surviving wolves in neighbouring

packs were strategically vaccinated in a cordon sanitaire, to

prevent the spread of rabies along the narrow valley `corridors' used by

the wolves; this intervention was successful in halting the spread of the

disease5, 6. Further modelling demonstrated that, even if

carcass detection rates fell as low as 20%, there would be sufficient time

to implement a reactive corridor vaccination campaign triggered by the

detection of two carcasses in a rabies outbreak6.

References to the research

1. Sillero-Zubiri C, King AA, Macdonald DW. (1996) Rabies and mortality

in Ethiopian wolves (Canis simensis). Journal of Wildlife Diseases

32: 80-86. doi: 10.7589/0090-3558-32.1.80 First published evidence

of confirmed deaths from rabies amongst Ethiopian wolves.

2. Laurenson K, Sillero-Zubiri C, Thompson H, Shiferaw F, Thirgood S,

Malcolm J. (1998) Disease as a threat to endangered species: Ethiopian

wolves, domestic dogs and canine pathogens. Animal Conservation 1:

273-280. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-1795.1998.tb00038.x Paper confirming

dog-borne diseases as a major threat to the Ethiopian wolf.

3. Haydon DT, Laurenson MK, Sillero-Zubiri C. (2002) Integrating

epidemiology into population viability analysis: Managing the risk posed

by rabies and canine distemper to the Ethiopian wolf. Conservation Biology

16: 1372-1385. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1739.2002.00559.x Paper

reporting on the results of computer-based modelling, demonstrating

that rabies vaccination levels of below 40% were likely to be

effective in preventing extinction.

4. Marino J, Sillero-Zubiri C, Johnson PJ, Macdonald DW. (2013) The fall

and rise of Ethiopian wolves: a natural experiment on the regulation of

populations of social carnivores. Animal Conservation doi:

10.1111/acv.12036 Paper reporting wolf population recovery and

social effects on population growth.

5. Randall DA, Williams SD, Kuzmin IV, Rupprecht CE, Tallents LA, Tefera

Z, Argaw K, Shiferaw F, Knobel DL, Sillero-Zubiri C, Laurenson MK. (2004)

Rabies in endangered Ethiopian wolves. Emerging Infectious Diseases 10:

2214-2217. doi: 10.3201/eid1012.040080 Initial report on the

management of the 2003-04 rabies outbreak amongst Ethiopian wolves.

6. Haydon DT, Randall DA, Matthews L, Knobel DL, Tallents LA, Gravenor

MB, Williams SD, Pollinger JP, Cleaveland S, Woolhouse MEJ, Sillero-Zubiri

C, Marino J, Macdonald DW, Laurenson MK. (2006) Low-coverage vaccination

strategies for the conservation of endangered species. Nature 443:

692-695. doi: 10.1038/nature05177 Paper reporting on the successful

implementation of the cordon sanitaire vaccination approach with

<40% of wolves inoculated against rabies during an outbreak.

Funding for research: Research since 1993 has been supported by

~£200,000 a year in grants, primarily from the Born Free Foundation and

the Frankfurt Zoological Society.

Details of the impact

The key contribution of the research led by Sillero-Zubiri has been to

provide robust, detailed evidence of the specific threats facing the

Ethiopian wolf. This evidence has enabled proper strategic planning for

the wolf's conservation and secured funds to implement effective

protection programmes, within which vaccination against rabies has played

the key role.

The first phase of the research documenting the importance of rabies as a

source of mortality in Ethiopian wolves1 catalysed several new

and important conservation actions. It led immediately to the species

being reclassified as Critically Endangered by the IUCN Red List of

Threatened Species7, and resulted in the first Ethiopian wolf

action plan (drawn up by the IUCN/SSC Canid Specialist Group8).

It also led to the establishment of the Ethiopian Wolf Conservation

Programme (EWCP), a science-driven conservation initiative that has gone

on to play a crucial role in the protection of the wolf and its habitat9,10,11.

EWCP implemented a campaign of rabies vaccination in local dogs (later

including canine distemper virus), aiming to inoculate 70% of the dog

population around wolf habitats; since 1996 more than 62,000 dogs have

been vaccinated. Ethiopian wolves had been protected by law since 1974;

due to their rarity the authorities were reluctant to authorize any

management requiring handling or vaccination of the wolves themselves.

Thanks to the compelling evidence provided by the underpinning research

carried out by Sillero-Zubiri and colleagues, immediate funding and

federal permission was forthcoming for the vaccination campaign that

neutralized the 2003 rabies epizootic; vaccination began a mere two weeks

after rabies was identified in the wolf population12.

Confirming the success of this strategy the species was uplisted to

Endangered from Critically Endangered by the IUCN in 20047.

The vaccination approach developed by creating a protective barrier or cordon

sanitaire of vaccinated wolf packs was deployed again in August 2008

when a major rabies outbreak hit the wolves in the Bale Mountains. The

Ethiopian authorities immediately approved an emergency vaccination

campaign, and 98 wolves were vaccinated, using a more refined and

systematic approach than previously, targeting the dominant pair to

preserve breeding units. Vaccination was associated with successfully

containing disease to the original outbreak (Fig 1)10-13.

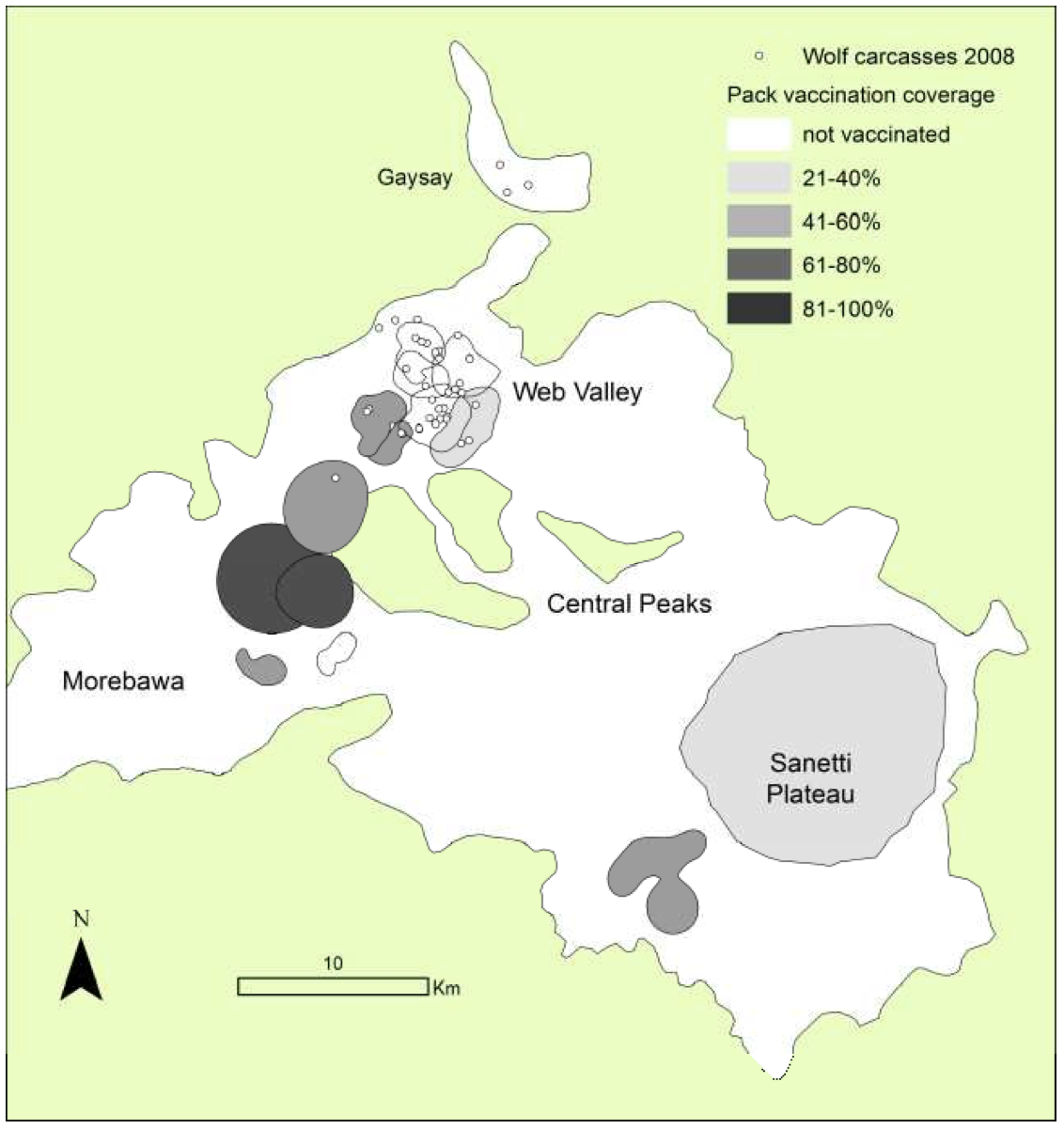

Figure 1: Distribution of wolf carcasses found in 2008 in relation to historical pack vaccination coverage. As predicted by modelling low

coverage vaccination in surrounding packs was effective in restricting the spread of rabies outside the initial

outbreak in Web Valley in 2008.

Figure 1: Distribution of wolf carcasses found in 2008 in relation to historical pack vaccination coverage. As predicted by modelling low

coverage vaccination in surrounding packs was effective in restricting the spread of rabies outside the initial

outbreak in Web Valley in 2008.

A consequential impact of the implementation of this research has been on

the local people who co-exist with the wolves. Some 8,500 households with

12,500 dogs live in and around wolf habitats in the Bale Mountains,

largely engaged in subsistence farming and grazing of livestock9,14.

Dogs are essential to local people for herding and also for consuming

human waste, but pose the greatest threat to wolves as vectors of canine

diseases. EWCP's ongoing domestic dog rabies vaccination campaign results

in significant economic and health benefits for local communities12,

which otherwise lose livestock to rabies and are also vulnerable to the

disease themselves. The incidence of rabies in humans in villages where

dogs were not vaccinated was up to five times higher than in villages

where dogs were vaccinated14.

The protection of the Afroalpine ecosystem, part of the Eastern

Afromontane biodiversity hotspot, has increased due to the attention

focussed on the Ethiopian wolf through this research. The efforts of EWCP

and partner Frankfurt Zoological Society have helped to extend the areas

designated as protected areas, with consequent impact for other rare

endemic species. As a result, the amount of suitable wolf habitat that is

protected has increased from 40% in 2000 to 87% in 201115. The

tourism value of the wolf is also important; wildlife tourism in Ethiopia

is increasing, with associated benefits to the Ethiopian economy (most of

the 2,000 people trekking in Bale each year come to see wolves). EWCP

provides other economic benefits through capacity-building and

conservation jobs within the Ethiopian conservation community (for

example, EWCP has funded 8 MSc and 2 PhDs by Ethiopian students). EWCP

employs 36 field staff, of whom 5 work for the Vet team vaccinating dogs

and wolves; 16 wolf monitors and Wolf Ambassadors monitor wolf

populations, in order to ensure a swift response to rabies outbreaks9,15.

As the apex predator in the Ethiopian highlands, the Ethiopian wolf has

an important role as a flagship species for Afroalpine biodiversity:

conservation of the species translates into the protection and maintenance

of habitats and ecological processes. The vaccination strategy developed

by Oxford University researchers has led both to the continued survival of

the wolf as well as associated benefits for local people. There is now a

robust National Action Plan in place for the wolf15, and the

current active level of research, together with the strong partnership of

Ethiopian and international organisations involved, will ensure that

conservation actions can be adapted to changing circumstances. The example

provided by this initiative, of a science-led conservation programme which

delivers timely targeted actions, offers a blue-print to similar

conservation challenges elsewhere16.

Sources to corroborate the impact

- IUCN Red List entry for the Ethiopian wolf, including a history of its

status. The species was reassessed in 2011, and on the basis of response

to vaccination and resulting population recovery, Endangered status was

upheld: http://www.iucnredlist.org/details/3748/0

- Status and species conservation action plan for the Ethiopian wolf,

prepared by the IUCN/SSC Canid Specialist Group in 1997: http://canids.org/PUBLICAT/EWACTPLN/ewaptoc.htm

- EWCP Annual Report (2013). http://www.ethiopianwolf.org/publications/EWCP-Annual-Report-April-2013.pdf

Evidence of community education programmes, wolf vaccination

programmes and new areas under protection.

- Letter from Ethiopia Country Director, Frankfurt Zoological Society

(held on file), confirming the importance of research and

intervention in controlling recent rabies epizootics.

- Letter from Director Born Free Foundation Ethiopia (held on file), confirming

importance of vaccination strategy in containing 2008 & 2009

rabies epizootics.

- Letter from Ethiopia's Chief Veterinary Officer (up to 2011);

currently FAO Director Animal Production & Health Division, Rome

(held on file).

- Letter from Head of Wildlife Zoonoses and Vector-borne Disease Group,

Animal Health and Veterinary Laboratories Agency (AHVLA), UK (held on

file), stating support for vaccination strategies developed in

underpinning research.

- Report on research carried out by Abera Yilma (MSc Diss.) into the

impact of EWCP rabies vaccination of dogs on local people:

http://www.ethiopianwolf.org/publications/JeedalaGazette_july09.pdf

demonstrating no human casualties in wards where vaccination took

place, and lower livestock losses to disease, when compared with

wards without vaccination.

- Strategic Plan for Ethiopian Wolf Conservation, prepared by the

IUCN/SSC Canid Specialist Group in December 2011. http://www.ethiopianwolf.org/SPEWC.pdf

Includes evidence of the scope of dog vaccination campaign, and of

range extension, resulting from research findings.

- Letter from Co-Chair IUCN/SSC Wildlife Health Specialist Group (held

on file), stating opinion that research has enabled a rare success

in veterinary intervention in wildlife conservation.