Changing the way government identifies small areas of need and distributes funding in the UK and beyond

Submitting Institution

University of St AndrewsUnit of Assessment

Geography, Environmental Studies and ArchaeologySummary Impact Type

SocietalResearch Subject Area(s)

Medical and Health Sciences: Public Health and Health Services

Economics: Applied Economics

Studies In Human Society: Policy and Administration

Summary of the impact

Research into more accurate methods for measuring deprivation and `need'

at the neighbourhood, `small area level', has led to older methods being

abandoned. This has shaped government policy and practice, leading to the

UK, local and central government changing where, geographically, to focus

millions of pounds of spend. Our methods (Index of Multiple Deprivation

(IMD) and Health Poverty Index (HPI)) are now used extensively in public,

political and media discourses as the main reference point for any

discussion of the distribution of need across the UK. The IMD has now also

been adopted by the governments of South Africa, Nambia and Oman.

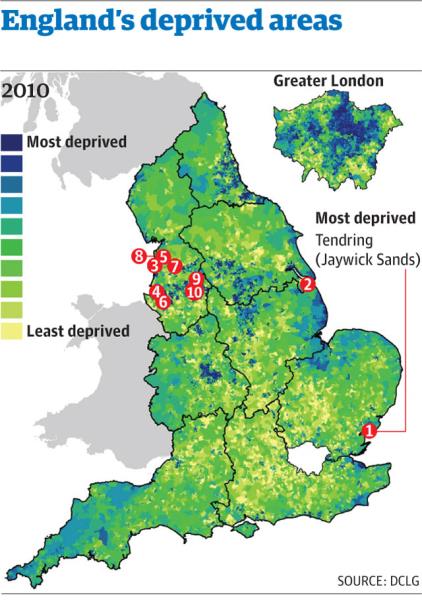

Source: The Guardian http://www.theguardian.com/news/datablog/2011/mar/31/deprivation-map-indices-multiple#_

Source: The Guardian http://www.theguardian.com/news/datablog/2011/mar/31/deprivation-map-indices-multiple#_

Underpinning research

Prior to our work, small area measures of need had been facing mounting

criticism. These criticisms focused on both their methodological

shortcomings and their weak theoretical foundations. The reliance on the

UK census meant, for example, that the measures could only be produced

every 10 years. The census also had few direct measures of the dimensions

of society that were of interest, such as poverty, disability or premature

mortality. These indicators were typically combined in a fairly

atheoretical manner, with indicators often haphazardly brought together

with equal weightings. They were also calculated for geographical areas

that varied considerably in size and homogeneity. As the aim was often to

produce a measure that could be used to judge whether different areas

should receive extra funding, the comparison of areas of very different

size was highly problematic.

A programme of research at the Universities of Oxford and St Andrews,

demonstrated the accuracy of a different approach to the measurement of

small area need within appropriate geographies over the last 13 years. We

highlight the parts of the research that were carried out at St Andrews;

led by Dr C. Dibben (Reader, 2004 onwards), Prof. R. Flowerdew (Professor,

2000- 2012) and Dr Z. Feng (Senior Research Fellow, 2000 onwards). The

research has focused on the following main areas:

1. Using administrative data to measure small area `need' on a regular

basis

It demonstrated for the first time in the UK that small area need could

be reliably and validly measured using administrative data. The St Andrews

work focused particularly on measuring the health of areas and groups for

the IMD and wide range of indicators for the HPI. Published in 2006, 2008

[1,2].

2. Methods for modeling small area `need' where no direct indicators

exist

For some important characteristics of an area (e.g. rate of smoking -

HPI), groups (eg emergency admissions amongst ethnic minorities - HPI) or

the whole index (South African IMD) there are no direct small areas

indicators available. We therefore developed a synthetic modeling

technique to estimate these missing characteristics. Published in 2008,

2010 [2,3].

3. How to produce small areas of similar population size and

homogeneity.

We developed a method for creating small area geography for the Scottish

IMD through the use of spatial modelling and complex geoinformatic

algorithms to build homogenous areas with similarly sized populations.

Published in 2007 [4].

4. How to combine indicators, into an index, in a theoretically sound

manner.

Using different modelling techniques and eliciting public opinions

(revealed preference and discrete choice) we derived empirically validated

weightings, for the IMD, with which to combine small area measures. Prior

to this weights had been more arbitrarily assigned. Published in 2007 [5].

References to the research

These key research papers have been assessed both through peer review and

a large number of official government consultation processes, policy

forums, Statistical Agency reviews and critical discussion with interest

groups. These measures continue to be widely used and this is indicative

of the confidence the UK has in the methodology, i.e. that it is

internationally excellent in terms of originality, significance and rigour

or better.

1. Noble, M Wright, G Smith G and Dibben, C (2006) Measuring Multiple

Deprivation at the Small Area Level. Environment and Planning A 38

169-185. doi: 10.1068/a37168

2. Dibben, C, Watson, J., Smith, T., Cox, M., Manley, D., Perry, I.,

Rolfe, L., Barnes, H., Wilkinson, K., Linn, J., Liu, L., Sims, A., and

Hill, A. (2008) The Health Poverty Index. The NHS Information Centre.

Leeds, UK. http://www.hpi.org.uk/

Details of the impact

The research described above convinced UK government departments to

invest in multiple editions of the Index of Multiple Deprivation (IMD) and

the Health Poverty Index (HPI). These have had considerable impact:

[1] changing where the government (national and local) allocates funding

— leading to investment in areas of genuine need,

[2] being the main point of reference for parliamentary debates on the

geographical distribution of deprivation across the UK — impacting policy

in UK,

[3] used extensively in the media in articles about geographical

inequalities across the UK — and therefore have influenced the public

understanding of patterns of need,

[4] as a way children are taught about patterns of `need',

[5] has been adopted by a number of countries across the world.

The IMD "have had a huge impact in terms of both reach and

significance. The impact has been so great that it is almost hard to

remember what life was like before they existed ..the SIMD [IMD in

Scotland] are certainly the standard which are extremely widely used by

a very wide range of users.... The benefits of this have been huge."

(Senior manager, National Records of Scotland) [S1].

(1) In resource allocation and policy decision making across the UK

"The Indices of Multiple Deprivation and its component indices are

probably the main mechanisms used in government at the moment to

distinguish between small areas for the purposes of analysing area

change, monitoring performance, setting targets and allocating funding."

[S6]

"The Indices of Multiple Deprivation (IMD) are used extensively to

analyse patterns of deprivation and inform the identification of areas

by local and central government that would benefit from special

initiatives or programmes and as a tool to determine eligibility for

specific funding." [S7]

About 1% of all government spending per year is allocated using

the IMD - ~£ 7 billion per year (author's calculation). The IMD

when first used led to considerable change in where resources were being

allocated across the UK, in particular it saw resources moving from some

parts of London to deprived parts of the North East and North West of

England (The Association of London Government calculated this change at

£265 million leaving London per year). The fact that the IMD is accepted

as an accurate measure of need, despite these large changes in where

funding was allocated, is strong evidence that it is redirecting resources

to areas of real need.

The IMD is also used extensively in local government [S2-S5]. For example

for Falkirk Council, it "is of major significance to us. We use

it to target resources, e.g. young people who would be eligible for

employment training programmes. We use it to identify areas of need. It

has on occasion been a factor in defining service delivery areas to

ensure that our areas of deprivation are not concentrated in one

particular service delivery area" (Senior manage Falkirk Council).

[S5]

The Improvement and Development Agency argue that the HPI is a "web

based tool covering all local authority districts in England... Rather

than being a tool for monitoring inequalities and evaluating the

effectiveness of interventions, [it is] an essential summary at the

start of the decision-making process as part of assessing needs and

facilitating discussion within local partnerships on local priorities."

[S8]

(2) In the way politicians discuss the geographical patterns of `need'

across the UK

- The IMD has consistently been central to debates at a national level —

a search of Hansard reveals 402 occasions in the last 10

years when it has been part of debates or parliamentary questions — this

level of reference has been consistent in the period since 2008.

- It is used in evidence for select committees, e.g. House of Commons

2011 Communities and Local Government Committee Regeneration, 2011 the

House of Lords Select Committee on HIV and AIDS in the United Kingdom.

[S9]

James Wharton MP, for example, when questioning civil servants during the

Public Accounts Committee 2010 review of health inequalities uses

statistics based on the IMD to "find that 52% of the deprived areas are

not within the Spearheaded areas, so it seems not only that where we are

or have been targeting we have picked up some areas that are perhaps not

in as desperate a need as others, but then you are missing out a huge

chunk of deprived areas which could benefit from this." [S10]

The IMD is a tool for political accountability. David Walker (former

director of communications at the Audit Commission) writes that the

public should "laud a decision to go ahead with the publication of the

latest IMD figures — because they redirect

attention to the huge disparity of resources and social conditions

between England's local areas....Rich boroughs might,

privately, aspire to get rid of their poor residents, and housing

benefit changes may help achieve that. But the IMD shows councils

cannot, for the foreseeable future, escape their fate as instruments of

social justice." [S11].

(3) In the way journalists describe geographical patterns of `need'

across the UK

- A search of the BBC website reveals its use in 131

articles referencing it and on the Guardian website 61 times

in the last ten years.

- A search using Google reveals 1,000+ references to it on local

government reports, websites, newspaper articles etc. Of these 1,000,

about 500 were referenced in published books, reports.

For example an article in the Guardian, 14 November 2012 "Analysis

of the data by the Guardian reveals that in the 50 worst councils

affected by the government's decision to slash local authority budgets

from 2010, the average cut was £160 per head. This group included the

poorest populations in Britain — such as the most deprived council in

the country, Hackney, and struggling urban areas of the north such as

Liverpool, Rochdale and South Tyneside." [S12] is typical of the way

debate and discussion is framed using the IMD.

(4) As a way children are taught about patterns of `need' across the

UK

The IMD is used in A level geography teaching. For example, the IMD is

part of the Edexcel AS geography syllabus. Edexcel, one of the five main

UK exam boards, uses it to enable children to explore the theme of places

needing to `rebrand themselves' Field Studies Council). Therefore

impacting how children understand the world around them.

(5) The IMD and Health Poverty Index methodology is now being adopted

by other countries around the world

- A number of versions have been produced for the Department for Social

Development in South Africa 2010 [3].

- The IMD methodology has also been adopted by Namibia and Oman.

-

The

Health Poverty Index methodology was adopted by the Irish

Public health Observatory in 2008.

Sources to corroborate the impact

Archived correspondence corroborate the extensive use of IMD in

respective organisations

[S1] Head of household estimates & projections branch National

Records of Scotland

[S2] Principal Information Analyst, Information Services Division (ISD),

NHS National Services Scotland

[S3] Senior Planning Analyst, Development and Regeneration Services,

Glasgow City Council.

[S4] Improvement and Organisational Development Project Officer, Argyll

and Bute Council.

[S5] Research and Information Leader, Falkirk Council

Reports/ papers

[S6] Lupton, Tunstall, Fenton and Harris (2011) Using and developing

place typologies for policy purposes, A report prepared for the Department

of Communities and Local Government London. http://webarchive.nationalarchives.gov.uk/20120919132719/http://www.communities.gov.uk/documents/corporate/pdf/1832148.pdf

[S7] Atlas of Deprivation 2010, Office for National Statistics http://www.ons.gov.uk/ons/rel/regional-trends/atlas-of-deprivation--england/2010/atlas-of-deprivation-2010.html

[accessed 22/02/2012]

[S8] Campbell F. Local public health intelligence. In: Campbell F,

Improvement and Development Agency, editors. The social determinants of

health and the role of local government. 2010.

http://www.local.gov.uk/c/document_library/get_file?uuid=eb92e4f1-78ad-4099-9dcf-64b534ea5f5c&groupId=10180

[S9] House of Commons Communities and Local Government Committee

Regeneration. Sixth Report of Session 2010—12 1st September the House of

Lords Select Committee on HIV and AIDS in the United Kingdom.

[S10] Public Accounts Committee, Tackling Inequalities in Life Expectancy

In Areas With The Worst Health And Deprivation 2010.

[S11] David Walker (2011) Mapping out needs, LocalGov.

http://www.localgov.co.uk/index.cfm?method=news.detail&id=98095

[S12] Randeep Ramesh (2012) Council cuts 'targeted towards deprived

areas'

http://www.guardian.co.uk/society/2012/nov/14/council-cuts-targeted-deprived-areas

http://www.publications.parliament.uk/pa/cm201011/cmselect/cmpubacc/c470-i/c470-i.htm