Design governance in the built environment: Facilitating the use of design codes

Submitting Institution

University College LondonUnit of Assessment

Architecture, Built Environment and PlanningSummary Impact Type

SocietalResearch Subject Area(s)

Medical and Health Sciences: Public Health and Health Services

Summary of the impact

Work by Carmona et al has supported the national drive for better design

in the built environment, helping to mainstream ideas about the importance

of urban design and develop tools for design governance. A major strand of

this research has focused on the use and potential of design codes in

England, and has been a major contributor to their widespread adoption. As

a result, by 2012, some 45% of local authorities and 66% of urban design

consultants had used design codes.

Underpinning research

From the mid-1990s UK government policy took a turn towards more active

promotion of better design in the built environment. Over the following

decade, research in the UCL Bartlett School of Planning (BSP) provided

much of the underpinning research supporting this shift in the areas of

design value, street design, public space management, design policy and

guidance, the measurement of quality, and the use and utility of design

codes. This latter work, led by Professor Matthew Carmona between 2003 and

2012, exemplifies the design governance research at UCL.

Following interest expressed in the potential of design codes by national

government, and consternation in the architectural press about the limits

this was perceived to place on design freedom, Carmona led a review of the

use and potential of design codes in 2003-04. This study built on

Carmona's earlier research on design guidance at UCL and established an

analytical framework that moved the discussion away from a preoccupation

with aesthetics [a]. Instead, it set the debate on design coding

within a larger four-part framework that focused on the fundamental issues

of:

- residential development process;

- key contexts which impact on design coding (i.e. site, policy, market,

stakeholder and regulation);

- the components of place shaped by codes; and

- potential outcomes from coding (better quality, certainty of process,

integration of stakeholder inputs, community engagement, and speed of

planning).

Evaluating each of these issues, and their inter-relationships, was vital

if the true impact of coding was to be fully understood.

It was within this framework that a full-scale national pilot programme

to evaluate design coding was commissioned from CABE by Government,

beginning in 2004 [b]. This utilised a research methodology

developed by Carmona in which each element of the analytical framework was

interrogated via seven large scale pilot projects around the country over

an 18-month period from 2004-05, alongside nine detailed case studies of

coded projects that were already being built. By way of comparison, four

schemes that did not use coding, but used other forms of detailed design

guidance, were also studied. UCL researchers were embedded within each of

the design/ development teams to observe and record progress and to

interview all key stakeholders at different stages of the coding process.

Ultimately, the results were drawn together by Carmona who authored the

research report [b] published by the Department of Communities and Local

Government (DCLG). This resulted in the associated academic publications [a]

and [d], the latter of which reviewed and revealed the potential

for codes to bring stakeholders together in a more consensus based

development process.

Carmona was subsequently commissioned by DCLG to author a practice guide

for professionals in order to promote the use of design coding in practice

and disseminate the research findings. Preparing Design Codes, A

Practice Manual remains the key source for practitioners preparing

design codes in the UK today [c]. In effect the guide establishes

when and when not to use codes and defines an `optimum' design coding

processes based on a developed version of the original analytical

framework. The process has now become the standard across the UK as

revealed in a follow-on project for the Urban Design Group six years

later, in 2012. This latest research conducted by Carmona and published in

Design Codes, Diffusion of Practice in England involved a national

survey of urban design practitioners and local planning authorities [e],

and demonstrated the national take-up of coding, following the original

research, as an innovation in mainstream development practice, as will be

shown below.

References to the research

[a] Carmona, M., Marshall, S. & Stevens, Q. (2006) `Design

Codes, Their Use and Potential', Progress in Planning, 65 (4):

201-290. [DOI: 10.1016/j.progress.2006.03.008]

Heavily cited (32 in Google Scholar); Commended (joint runner-up) for the

AESOP Prize Best Paper in 2007.

[d] Carmona, M. (2009) `Design Coding and the Creative, Market and

Regulatory Tyrannies of Practice', Urban Studies, 46 (12):

2643-2667. [DOI: 10.1177/0042098009344226]

The quality of the underpinning research is demonstrated by the following

grants:

• Carmona, M. (PI), The Development and Use of Design Codes in the UK,

CABE, November 2003 — June 2004 (£52,332). This grant led to output [a]

above.

• Carmona, M. (PI), Design Code Pilot Programme Research and

Evaluation, ODPM, June 2004 — November 2005 (£153,502). This grant

led to outputs [b] and [d] above.

• Carmona, M. (PI), Design Codes A Good Practice Guide, CLG,

March — June 2006 (£40,000). This grant led to output [c] above.

• Carmona, M. (PI), Design Codes, Diffusion of Practice in England,

UCL / Urban Design Group, May — September 2012 (£5,000). This grant led to

output [e] above.

Details of the impact

A combination of UCL research between 2004 and 2006, later follow-up

work, and dissemination through nearly 30 conferences and seminars in the

UK and worldwide from 2004-13 has established the effectiveness of design

codes in the delivery of high-quality residential design in England and

overseas. In the process, research by Carmona et al has become the primary

source for advice on the preparation of design codes for practitioners and

local authorities alike.

Change in policy and practice:

Research described in Section 2 provided the primary evidence base for

the direct endorsement of design codes in the Barker Review of Land

Use Planning (2006) (Recommendation 24 [1], and Planning

Policy Statement 3: Housing (2006), the UK government's strategic

housing policy for England. The latter recommended that `Local

Planning Authorities should ... promote the use of appropriate tools and

techniques, such as Design Codes', in order to `facilitate

efficient delivery of high quality development' [2; para 18].

It remained in force throughout 2006-12, with three editions, the most

recent of them in 2011. In 2012, all planning policy statements were

replaced by a unified National Planning Policy Framework which once again

directed that `Local planning authorities should consider using design

codes' as a means to `help deliver higher quality outcomes'

[3; para 59] — and all this despite wider simultaneous moves

towards deregulation.

The research work was widely referenced by the UK government and its

agencies, including:

- Policy and practice documents supporting a dimension of the research

that explored the designation of Local Development Orders (LDOs)

alongside design codes on the basis that they can speed up the planning

process whilst delivering design quality [d; Appendix 1].

Initially this found support in CLG Circular 01/2006, then in

the 2008 Killian Pretty Review of the planning system [4;

item 2.1.2].

- The Homes and Communities Agency (HCA) published Urban Design

Compendium 2 in 2009, which includes specific reference to the

underpinning UCL research on design codes:

`Research has found that it is sites such as these (large sites where

delivery is phased either over time or between different design teams)

that benefit most from the use of design codes.' The document thus

endorses the practice guide and goes on to summarise key findings from

the research regarding the benefits of design coding for stakeholders [5;

p. 128]

- The 2012 online guidance of ATLAS, the government funded independent

advisory service on large scale development, which advocates the use of

design coding in their work in order to fulfil one of their corporate

objectives, to improve the speed and quality of major housing

developments. In doing so they draw from the research to shape their own

advice to clients on the use of design codes, quoting Preparing

Design Codes: A Practice Manual [c] as `the key reference'

[6; item T2.9]. This emphasis is reflected in its discussion of

means to ensure design quality through case studies of successful

projects it has advised on, for example, a successful proposal in 2010

to develop west of Waterlooville in Hampshire with 3,000 homes. In this

case, ATLAS identified the early submission of design codes as a key

driver on quality and a catalyst in creating a conversation about design

[7].

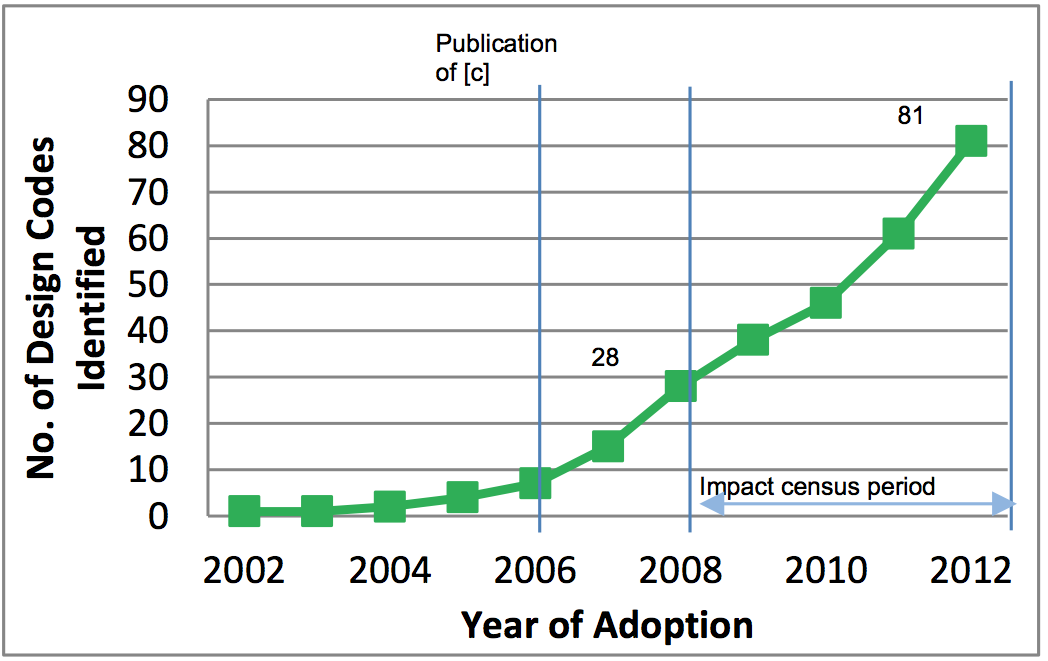

Adoption of design codes:

By providing the evidence base to advocate for design codes, and the

guidance on adopting them, the research has been hugely influential in

driving practice. This was demonstrated through research led by Carmona

for the Urban Design Group (UDG) in 2012, which tested the diffusion of

design coding as a tool in the development process, and revealed the scale

of this influence. From an almost standing start in 2003, by 2012 around

45% of local authorities (geographically spread across England) had used

design codes and 66% of urban design consultants had prepared them [8;

pp. 6-7]. From the data it was estimated that over 120 design codes

had been Impact census periodprepared between 2006 and 2012 (85% of these

after 2008), compared to a smattering before, with the rate of adoption

continuing to climb year on year [8; p. 2]. It was found that the

research and accompanying guidance was the primary source of advice on the

preparation and use of design codes by local authorities and private

practitioners alike — e.g. West Northamptonshire's 2009 Manual for

Design Codes; in Plymouth's 2009 Design Code Factsheet; or

the 2012 Design Codes for Strategic Development Sites within the

Cambridge Fringe Area [9].

Taken together, design codes now direct the development of many thousands

of houses over many thousands of acres across England. Taking just one

local authority as an example, since 2006 Swindon Borough Council has used

codes in all four of its major strategic housing sites at Wichelstowe,

Tadpole Farm, Commonhead, and New Eastern Villages, covering 14,580 new

homes on 1,000+ hectares of land [10].

The survey revealed a wide range of projects across England — from

Ashford to Carlisle — in which respondents reported that the `innovation'

of codes had enhanced both process and outcomes. Indeed, 93% of those who

used design codes reported they would do so again [8; p. 12]. By

2012, design codes were advocated in a quarter of local plans, and the

number was rapidly increasing, whilst a large majority of planning

authorities and urban design consultants who have had not yet used design

codes stated their intention to use them in the future. As one officer

said, `codes are the only way to get volume builders to develop out in

an appropriate integrated manner' [8; p. 12].

As a sign of this significant diffusion of design coding practice, the

UDG study revealed that private developers are now submitting unsolicited

design codes in large numbers as part of planning applications, indicating

how practice has become mainstreamed, whilst survey respondents reported

the following benefits of using the codes [8; pp. 1-2]:

- Improving design quality by tying down the `must have' design

parameters that hold the schemes together, and ensuring consistency in

the delivery of key site-wide design principles;

- Offering far greater certainly about outcomes and certainly to

developers about the process;

- Bringing key stakeholders together early in the process leading to

smoother working relationships and to a better understanding of

constraints from the start;

- Speeding up the reserved matters planning applications made in

connection with the successive phases of large development projects.

As one planner put it: `Well framed codes, based on a clear

understanding of the limits of the client's control and influence have

resulted in a clear uplift in quality, principally in the better

integration of complicated development sites or where the landownership

is a patchwork.' [8; p. 9].

Contributions by UCL research to policy are ongoing. The above diffusion

of practice was further advanced by a recommendation of the Taylor External

Review of Government Planning Practice Guidance (2012) that the

underpinning practice guidance should be incorporated into the new National

Planning Practice Guidance; this was duly done in August 2013 [11;

ID 26-032-130729].

The reach of these impacts was extended further when the research at UCL

by Carmona et al inspired the HOPUS consortium of universities and

municipalities in the European Union's URBACT programme to focus on the

use and potential of design codes as a tool for improving the

sustainability of housing development. As its `Lead Expert' through the

project's life (2008-10) Carmona advanced the principles and processes of

design coding developed during the research as a basis for local

investigations in Portugal, Italy, Poland, and The Netherlands, which

enabled HOPUS to assess the value of design coding, as well as the

conditions necessary for its success [12; p. 6]. In Poland, for

example, tests carried out in six cities led to the conclusion that design

coding offers a valuable tool to challenge development practice that is

typically driven by a private sector with little interest in design

quality [11; p. 205].

Sources to corroborate the impact

[1] Barker Review of Land Use Planning (2006) [http://bit.ly/19afVQE,

PDF].

[2] Planning Policy Statement 3: Housing (2006 / 2011, 4th

edition) [http://bit.ly/1hYNuXH, PDF].

[3] National Planning Policy Framework (2012) [http://bit.ly/17vEYKZ,

PDF, demonstrating the continuing relevance of the research through the

reflection in national policy].

[4] Killian Pretty review of the planning system [http://bit.ly/H5KBsl,

PDF, para 2.1.2, linking LDOs with design codes as advocated through the

research].

[5] HCA Urban Design Compendium 2 (2009, 2nd

edition) [http://bit.ly/19aiVfD, PDF,

p. 128, giving advice on design coding and endorsing the research].

[6] ATLAS website advice on design coding [http://bit.ly/1bBBhXs,

T2.9 endorsing the research].

[7] ATLAS case study of West of Waterlooville with design codes [http://bit.ly/1fFbrXa, PDF].

[8] Study [e] reviewed and subsequently published by the Urban

Design Group Executive Committee [http://bit.ly/1ar9CGc,

PDF, on the diffusion and relevance of design coding practice].

[9] Research as primary source of advice, e.g. Plymouth (2009) [http://bit.ly/1dCNPBV, PDF, p. 4]

and Cambridge (2012) [http://bit.ly/HqJWSu,

PDF, p. 4].

[10] Swindon Borough Local Plan 2026 (December 2012) [http://www.swindon.gov.uk/ep/ep-planning/forwardplaning/ep-planning-localdev/Documents/Local%20Plan%20Pre-Submission%20draft.pdf,

PDF, pp. 173-192].

[11] Continuing relevance of research in national guidance

demonstrated by inclusion in National Planning Practice Guidance on design

coding [http://bit.ly/1aQZkjW, August

2013) following Taylor Review recommendation (December 2012) [http://bit.ly/1hmvEQM,

PDF, Annex B].

[12] EU URBACT, Housing Praxis for Urban Sustainability (HOPUS) [http://bit.ly/16DGjPM, PDF].