Improving feline health through the worldwide application of infectious and genetic disease polymerase chain reaction assays

Submitting Institution

University of BristolUnit of Assessment

Agriculture, Veterinary and Food ScienceSummary Impact Type

TechnologicalResearch Subject Area(s)

Medical and Health Sciences: Medical Microbiology

Summary of the impact

Bristol University's School of Veterinary Sciences, a global leader in

feline medicine, was the first

UK centre to develop and commercially offer polymerase chain reaction

(PCR) and quantitative (q)

PCR assays to detect a range of feline infectious and genetic diseases.

Since 2008 there has been

a dramatic increase in the number of qPCR tests performed, with over

35,000 tests carried out

between 2008 and 2013. The results of genetic testing have informed

breeding programmes and

resulted in a reduced prevalence of genetic disorders such as polycystic

kidney disease (PKD).

The results of testing for infectious diseases have informed diagnosis and

treatment modalities

and, together with the genetic testing, have contributed to significant

improvements in feline

health and welfare. This work has also generated commercial income

in excess of £1.7M, which

has been used to further research into feline infectious and genetic

diseases.

Underpinning research

The underpinning research was conducted by Dr Chris Helps (Research

Fellow 2001-2007; Senior

Research Fellow 2007-present) and Dr Séverine Tasker, (PhD Student

1999-2002; Lecturer in

Small Animal Medicine 2002-2006; Senior Lecturer in Small Animal Medicine

2006-2013; Reader

in Feline Medicine 2013-present).

Early industry funded studies (2001-2003) by Dr Chris Helps resulted in

the development of feline

herpesvirus [1,4], feline calicivirus [4], Chlamydophila felis

[1,4] and Bordetella bronchiseptica [4]

qPCR assays and their use in samples from over 1700 cats from 218 European

catteries.

Subsequent studies by Dr Séverine Tasker (2001-2002), funded by charitable

trusts, led to the

development of qPCR assays to detect two species of feline haemoplasmas

[2]. More recent

studies (2002-2013) by Drs Chris Helps and Séverine Tasker, funded by

industry and charitable

trusts, led to the development of qPCR assays for the detection of feline

immunodeficiency virus

(FIV) and feline leukaemia virus (FeLV). To date 12 qPCR assays have been

developed for a

range of important feline infectious diseases including the agents causing

cat `flu', conjunctivitis

and anaemia, and 10 PCRs have been developed to detect a range of genetic

diseases such as

kidney [5] and metabolic disorders [6].

Many of the PCR assays described above have been used in national and

international research

projects to study the pathogenesis and determine the prevalence of

infectious organisms in cat

populations. Other research studies using these PCR assays have identified

risk factors for

infection and described the in vivo kinetics of infection with

feline haemoplasmas, monitored

responses to antibiotic treatment [3] and evaluated the potential routes

of transmission. Many of

the PCRs to detect inherited genetic diseases have been used to evaluate

their prevalence in cat

populations [5,6] and to monitor the change in prevalence over time. From

2002-2013, over 30

papers have been published in peer-refereed scientific journals.

Important findings from this research

- PCRs are very sensitive and specific methods for the diagnosis of

feline infectious and

genetic diseases [1,2,4].

- Feline herpesvirus, feline calicivirus, Chlamydophila felis

and Bordetella bronchiseptica are

significantly correlated with upper respiratory tract disease in cats

[4]. Risk factors

associated with these diseases in cats were poor hygiene, contact with

dogs with upper

respiratory tract disease and large numbers of cats housed together.

- From 2005-2013, due to genetic testing and selective breeding, there

has been a 90%

reduction in the prevalence of the mutation causing PKD in the cat

population tested.

- Older male non-pedigree cats are more likely to be infected with

haemoplasmas.

- The feline haemoplasma, Mycoplasma haemofelis, shows cycles of

infection in vivo.

- Marbofloxacin is an effective antibiotic treatment for feline

haemoplasma infection.

- Doxycycline is an effective antibiotic treatment for feline

chlamydophila infection

- Saliva is a possible mechanism of transmission of feline haemoplasmas.

References to the research

[1] Helps, C.R., Reeves N.A., Egan, K., Howard, P. and Harbour, D.A.

(2003) Detection of

Chlamydophila felis and feline herpesvirus by multiplex real-time

PCR. Journal of Clinical

Microbiology. 41:2734-2736. DOI: 10.1128/JCM.41.6.2734-2736.2003

[2] Tasker, S., Helps, C.R., Day, M.J., Gruffydd-Jones, T.J. and Harbour,

D.A. (2003) Use of

real-time PCR to detect and quantify Mycoplasma haemofelis and `Candidatus

Mycoplasma

haemominutum' DNA. Journal of Clinical Microbiology. 41:439-441. DOI:

10.1128/JCM.41.1.439-441.2003

[3] Tasker, S., Helps, C.R., Day, M.J., Harbour, D.A., Gruffydd-Jones,

T.J. and Lappin, M.R.

(2004) Use of a Taqman PCR to Determine the Response of Mycoplasma

haemofelis

Infection to Antibiotic Treatment. Journal of Microbiological Methods.

56:63-71. DOI:

10.1016/j.mimet.2003.09.017

[4] Helps, C.R., Lait, P., Damhuis, A., Björnehammar, U., Bolta, D.,

Brovida, C., Chabanne, L.,

Egberink, H., Ferrand, G., Fontbonne, A., Grazia Pennisi, M.,

Gruffydd-Jones, T., Gunn-Moore, D.,

Hartmann, K., Lutz, H., Malandain, E., Möstl, K., Stengel, C.,

Harbour, D.A. and

Graat, E.A.M. (2005) Factors associated with upper respiratory tract

disease caused by

FHV, FCV, C. felis and B. bronchiseptica in cats —

experience from 218 European catteries.

The Veterinary Record, 156:669-673. DOI: 10.1136/vr.156.21.669

[5] Helps, C.R., Tasker, S., Barr, F.J., Wills, S.J. and Gruffydd-Jones,

T.J. (2007) Detection of

the single nucleotide polymorphism causing feline autosomal-dominant

polycystic kidney

disease in Persians from the UK using a novel real-time PCR assay.

Molecular and Cellular

Probes. 21:31-34. DOI: 10.1016/j.mcp.2006.07.003

[6] Grahn, R.A., Grahn, J.C., Penedo, M.C.T., Helps, C.R. and Lyons, L.A.

(2012) Erythrocyte

Pyruvate Kinase Deficiency Mutation Identified in Multiple Breeds of

Domestic Cats. BMC

Veterinary Research. 8:207. DOI: 10.1186/1746-6148-8-207.

Grants : In addition to a number of small grants from charities,the

following larger grants have

supported research in this area.

[i] 2011-2014 PFIZER ANIMAL HEALTH. £105,000. Tasker, S., Helps, C.R.

& Stokes, C.R.

Feline haemoplasmas: cultivation & defining immunological responses.

[ii] 2007-2010 PFIZER ANIMAL HEALTH. £37,650. Tasker, S. & Helps,

C.R. Evaluation of

haemoplasma pathogenic determinants.

[iii] 2007-2010 UNIVERSITY OF BRISTOL STUDENT PHD SCHOLARSHIP for Barker

E.

£48,600. Tasker, S & Helps, CR. Evaluation of haemoplasma pathogenic

determinants.

[iv] 2006-2010 WELLCOME TRUST. £261,712. Tasker, S. & Helps, C.R.

Pathogenicity, in

vitro culture requirements, transmission and phylogeny of haemotropic

mycoplasmas.

[v] 2001-2003 INTERVET, The Netherlands. £50,000. Harbour, D.A. and

Helps, C.R.

Prevalence of feline pathogens in European catteries detected by real-time

PCR.

Details of the impact

Accurate diagnosis of infectious and genetic diseases is important for

the treatment and

management of cats by vets, as well as to inform breeding policy to reduce

the prevalence of

inherited genetic diseases. The infectious agents for which qPCR assays

have been developed

result in serious and welfare-compromising clinical signs in cats, which

can be fatal if these agents

are not detected and thus not treated appropriately. Upper respiratory

tract disease associated with

feline herpes virus, feline calcivirus, C. felis and B.

bronchiseptica cause ocular and nasal

discharge, pyrexia and anorexia, whilst haemoplasmas cause haemolytic

anaemia. The

retroviruses FIV and FeLV are immunosuppressive agents that are associated

with secondary

infections and neoplasia. The pioneering PCR assays described in the

underpinning research

section have led to significant commercial activity within Langford

Veterinary Services (LVS, a

wholly owned subsidiary of the University of Bristol), in excess of £1.7M

to date, and the following

clinical benefits for affected cats:

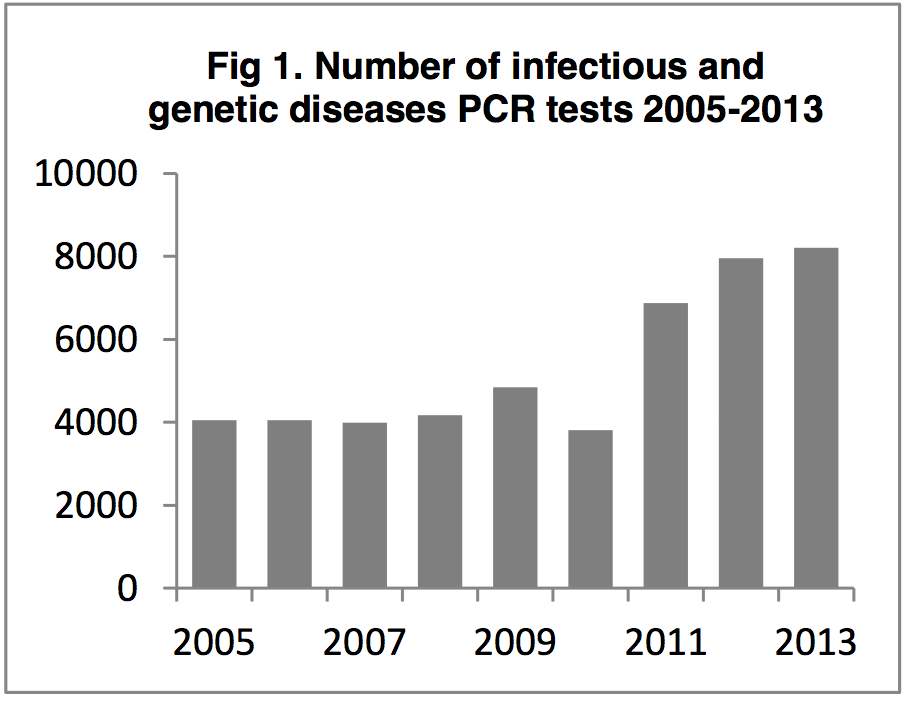

An increase in the number of PCR tests

performed leading to specific treatments

The PCR assays are offered to vets and cat breeders

troughout the UK and Europe [a]. By the end of

2013, more than 53,000 PCR tests will have been

performed on over 40,000 cats since testing began in

2002. We have seen a significant increase in the

number of PCR tests run, from ~4000 per annum in

2005-2008 to over 8000 per annum in 2013 [b]

(Figure 1). Accurate detection of feline infectious

agents leads to correct treatment protocols (e.g.

doxycycline for C. felis, antivirals for FHV infection,

marbofloxacin for haemoplasmas) and significantly

improves health outcomes for infected cats. It also allows for appropriate

management (e.g.

isolation of cats, barrier nursing, keeping cats indoors, vaccination of

in-contact cats) to prevent

disease transmission [j].

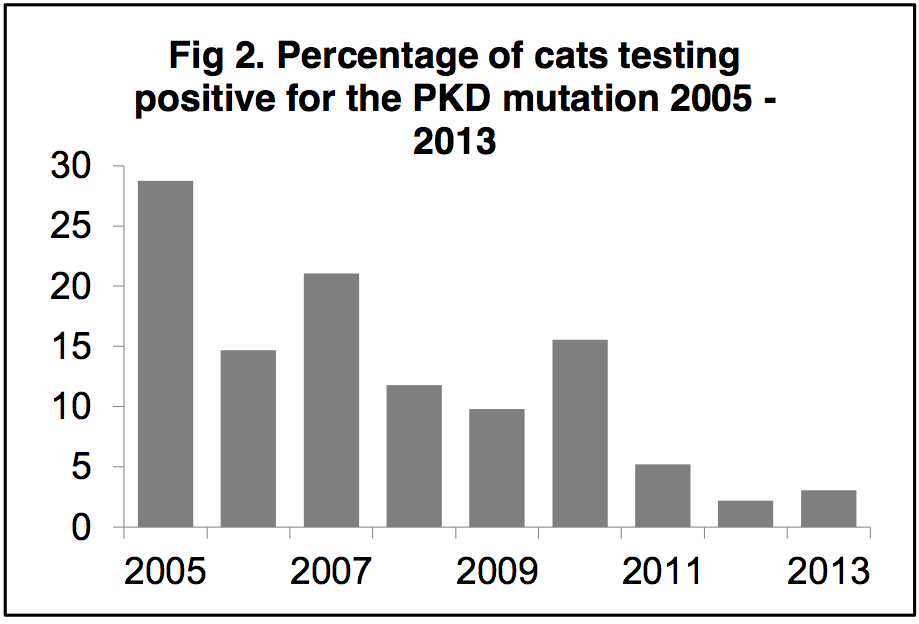

Reduction in the prevalence of inherited genetic

diseases

By genetic testing and selective breeding the

prevalence of inherited genetic disorders can be

reduced. Figure 2 shows the prevalence of the PKD

mutation in 4085 breeding cats, from 735 breeders,

tested between 2005 and 2013 [b]. There has been

a 90% reduction in the number of cats testing

positive for the PKD mutation over the 8 years

Bristol has been running the genetic test, such that

less than 5% of submitted cat samples were PKD

positive in 2013. This indicates that fewer cats will

develop chronic kidney disease due to PKD and

results in a positive impact on feline health and welfare [k].

As a result of the Bristol genetic testing service for cat breeders, Dr

Chris Helps has been asked by

the Governing Council of the Cat Fancy (GCCF), the main registration body

for pedigree cats in the

UK, to collaborate on developing breed group genetic disease test panels

[c]. These will form part

of the GCCF Breeder Scheme, which aims to promote responsible cat breeding

and reduce the

prevalence of inherited genetic diseases in pedigree cats.

Number of vets and breeders using the PCR testing service

Since 2009, 705 veterinary practices and 30 referral and University

diagnostic laboratories, both in

the UK and Europe [d], have submitted samples for feline infectious

disease qPCR testing,

showing that a significant proportion (735 out of 4562 (16%, as of 2011))

of UK veterinary practices

use these diagnostic tests. In addition, since 2005 over 1900 [e] cat

breeders across Europe have

submitted samples for genetic disease PCR testing and have used the

results to inform their

breeding policy, with the ultimate aim of reducing or eliminating

inherited genetic diseases in their

breeding lines and increasing feline health. The increase in the number of

infectious disease

samples submitted clearly shows that vets are using these assays, and

hence value the results for

diagnosing and treating cats. Worldwide Guidelines, which include this

Bristol research, are now

available for vets to use to direct therapy and management on the basis of

qPCR results [l,m].

Advice calls and dissemination of information

An audit of advice calls and emails undertaken over a typical week in

November 2012 showed that

32 vets and 10 cat breeders contacted the Diagnostic Laboratory and Feline

Centre regarding

feline infectious and genetic disease PCR testing [f]. This equates to over

2000 advice calls per

year and shows that a significant number of vets and breeders are

aware of and/or use the PCR

assays, value the results they obtain and benefit from talking to

clinicians and geneticists who can

help them interpret the results.

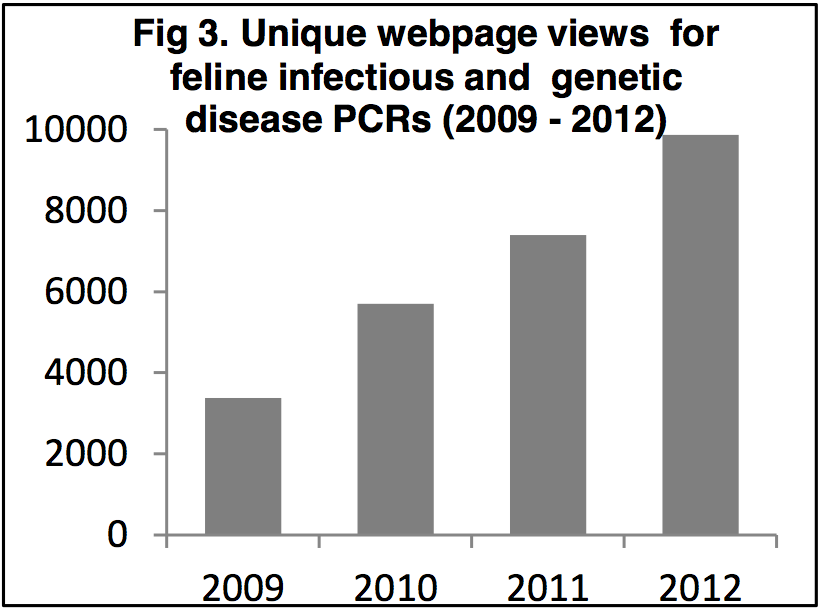

National and international interest in the infectious and genetic PCRs

Figure 3 shows unique page views for feline infectious

and genetic disease PCRs taken from the Langford

Veterinary Services website. Between April 2009 and

November 2012 there were over 26,000 unique page

views on 15 webpages, with the average number of

views increasing from ~3500 in 2009 to ~10,000 in

2012; a 285% increase in 3 years [g]. Looking at the

source of these unique page views shows that 41%

originated outside of the UK, with visits from 126

countries being logged [g]. This level of interest in

feline infectious and genetic disease PCRs shows

both the national and international impact of this work.

Through sharing reagents derived from the PCR assay development, a number

of other

international laboratories are now offering infectious disease testing by

PCR assays e.g. Iran,

Israel, New Zealand, Portugal, Sweden, Thailand, Turkey, Indonesia,

France, Australia, The West

Indies and USA, enabling cats worldwide to be tested for infectious agents

[h,i].

In conclusion, thanks to Bristol research, qPCR tests for feline

infectious and genetic diseases are

now widely used to benefit feline health and welfare both in the UK and

internationally. Clinical

guidance targeted at veterinary surgeons working in the UK and

internationally now also includes

recommendations to utilise these testing procedures as part of standard

practice [l,m] and the

GCCF is introducing breed-panel genetic testing in collaboration with

Bristol [c].

Sources to corroborate the impact

[a] LVS website, http://www.langfordvets.co.uk/diagnostic-laboratories/diagnostic-laboratories/pcr-acarus

(Corroborates molecular diagnostic testing service available in UK and

Europe)

[b] Excel spread sheets for Fig 1 and Fig 2 data, (data for

Figs1& 2, corroborating large number of

tests run and their change over time and decrease in cats testing

positive for PKD. Full

spreadsheet available via RED, Bristol University)

[c] Letter from the GCCF regarding collaboration and breed specific

genetic testing. (Corroborates

national importance of genetic testing and of Dr Helps' recognised role)

[d] List of veterinary practices, referral laboratories (including

Universities) and cat breeders

sending samples to LVS for disease testing. (Corroborates large number

of users of infectious

disease PCR testing in UK and Europe)

[e] Spreadsheet of cat breeders using the genetic testing service (Corroborates

impact on

behaviour of over 1900 breeders who have used genetic testing to screen

their cats)

[f] Spreadsheet showing advice calls in a typical week (Shows the

importance of qPCR testing and

result interpretation, and its impact on both the vets and breeders who

use the service)

[g] Unique views of the LVS website for the feline infectious and genetic

disease PCR tests (Data

for Fig 3, showing worldwide interest in PCR testing)

[h] Statements from commercial labs, local and international

collaborators. (Responses to

questionnaire describing the international impact of developing tests

with Bristol reagents)

[i] Contact 1, Universiti Putra, Malaysia. (Contact for testimonial

regarding international impact of

PCR test development)

[j] Contact 2, Field Veterinary Officer, Cats Protection, National Cat

Centre (Contact for impact of

infectious disease qPCR testing on cat health, disease treatment

decisions and transmission)

[k] UFAW website. http://www.ufaw.org.uk/POLYCYSTICKIDNEYDISEASEPERSIAN.php

(Describes impact

of genetic testing on disease reduction, quotes Bristol research)

[l] European Advisory Board on Cat Diseases (ABCD) Guidelines published

in Journal of Feline

Medicine and Surgery (2009) 11: Feline herpes virus (547-555), Feline

calicivirus (556-564),

FeLV (565-574) and C. felis (605-609). (Impact via

dissemination of information about PCR

testing as a recommended method)

[m] Canine and Feline Infectious Diseases by Jane E Sykes (2013).

Elsevier, Health Sciences Div.

Ch 5 Nucleic acid detection assays, Ch 22 FeLV, Ch 23 Feline respiratory

viral infections, Ch 33

Chlamydial infections, Ch 41 Hemoplasma infections. SBN 1437707955 (Impact

as for [l])