Preventing the gastroduodenal hazards of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and aspirin through widespread adoption of proton pump inhibitors

Submitting Institution

University of NottinghamUnit of Assessment

Clinical MedicineSummary Impact Type

HealthResearch Subject Area(s)

Medical and Health Sciences: Clinical Sciences, Pharmacology and Pharmaceutical Sciences

Summary of the impact

Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) are valuable analgesics,

but cause dyspepsia, ulcers and hospitalisation (UK: 3,500pa, USA:

100,000pa) for complications that can lead to death (UK: 400-1,000pa, USA:

16,500pa). Acid inhibition by proton pump inhibitors (PPIs), the only

widely accepted preventative strategy, was proposed and systematically

proved by studies from Nottingham. NICE now recommends PPIs for all

patients using NSAIDs and PPIs are central to all major international

guidelines. PPI co-prescription has increased worldwide (from 27.6% in

2008 to 44.1% in 2012, in the UK); and reduces the risk of hospitalisation

for gastrointestinal bleeding by 54% and symptomatic ulcer by 63%, thereby

preventing up to 540 deaths per annum in the UK.

Underpinning research

Scale of the problem: Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs

(NSAIDs) cause two clinically important gastroenterological problems —

ulcer complications (largely bleeding) which are relatively rare but

dangerous, and dyspepsia which is common, impairs quality of life and

restricts NSAID use. NSAIDs have an attributable rate of hospitalisation

of approximately 2.7-4.0 per 1,000 patient years in patients aged >60.

On the basis of this, prior to widespread adoption of proton pump

inhibitor (PPI) co-prescription, NSAIDs were conservatively calculated to

cause 3,500-4,000 hospitalisations and 400-1,000 deaths pa in the UK

[Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf, 2001;10:13-19]. In trials, between 13 and 31%

of patients report dyspepsia [Clin Ther 2010;32:667-677; BMJ

2009;339:b2538].

Nottingham's contribution: Much of the most reliable

epidemiological data that identified and quantified the GI risks of NSAIDs

emanated from the Department of Therapeutics under Professor Michael

Langman (1971-1987). Professor Chris Hawkey (Nottingham Digestive Diseases

Centre, 1983-present) then developed the translational models described

here, becoming a UK leader in this field. Hawkey also developed the

therapeutic interventions discussed, before their evaluation in clinical

trials.

Translational basis: Our translational facility enabled strategies

for mucosal protection and underlying mechanisms to be investigated.

Investigations were based on ex vivo pharmacology, mucosal injury,

spontaneous and induced bleeding and healing of mucosal breaches. Of more

than twenty strategies evaluated, use of omeprazole (first of the then

novel PPI class of drugs) appeared to be most effective. Omeprazole was

potent and reliable in its ability to virtually abolish mucosal injury,

measured as acute microbleeding.

Initial trials: This caused us to suggest to Astra that they

conduct trials with omeprazole in NSAID users, but these suggestions were

not taken up. Our team therefore collaborated with rheumatological and

gastroenterological colleagues in Nottingham and Glasgow to do a proof of

principle investigator-initiated study with the H2 antagonist famotidine.

This study showed that acid inhibition with high, but not standard, doses

of famotidine was effective in preventing and healing ulcers and treating

the dyspepsia caused by NSAIDs1.

Definitive omeprazole trials: This work provoked renewed interest

by Astra. As co-Chief Investigators, Professors Hawkey and Neville Yeomans

(Melbourne, Australia) developed and coordinated a large international

programme of three linked studies of primary and secondary prevention, and

ulcer healing, which the company funded2,3. These studies

showed that omeprazole had clear efficacy and tolerability advantages over

the H2 antagonist ranitidine and the prostaglandin analogue misoprostol,

which were used as comparators. This work authoritatively established the

effectiveness of PPIs for ulcer prevention, healing and maintenance, and

for symptom control, and this was reflected in the ensuing licensed

indications for omeprazole and, later, other PPIs. The nature and quality

of the team's academic relationship led Astra to support a pivotal

investigator-initiated trial of little commercial interest which was

important in showing H.pylori eradication to be insufficient as an

alternative strategy4.

Broadening the evidence: As co-Chief Investigators, Professors

Hawkey and Yeomans later reported similar finding with esomeprazole5,

and effectiveness was shown for other PPIs. Because the GI hazards of

aspirin were an important unmet need, Hawkey and Yeomans persuaded

AstraZeneca to support investigator-initiated studies that established

efficacy of PPI prophylaxis here too6, leading to a successful

regulatory claim for a combination preparation.

References to the research

1. Taha AS, Hudson N, Hawkey CJ, et al. Famotidine

for the prevention of gastric and duodenal ulcers caused by non-steroidal

anti-inflammatory drugs. N Engl J Med 1996; 334(22):1435-1439. http://dx.doi.org/10.1056/NEJM199605303342204

2. Hawkey CJ, Karrasch JA, Szczepanski L, et al.

Omeprazole compared with misoprostol for ulcers associated with

nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs. Omeprazole versus Misoprostol for

NSAID-induced Ulcer Management (OMNIUM) Study Group. N Engl J Med 1998;

338(11):727-734

http://dx.doi.org/10.1056/NEJM199803123381105

3. Yeomans ND, Tulassay Z, Juhasz L, Racz I, Howard JM, van Rensburg CJ,

Swannell AJ, Hawkey CJ for the ASTRONAUT Study Group. A

comparison of omeprazole and ranitidine for treating and preventing ulcers

associated with non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. N Eng J Med 1998;

338(11):719-726.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1056/NEJM199803123381104

4. Hawkey CJ, Tulassay Z, Szczepanski L, et al. Randomised

controlled trial of Helicobacter pylori eradication in patients

taking non-steroidal, anti-inflammatory drugs: The HELP NSAIDs Study.

Lancet 1998; 352(9133):1016-1021.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(98)04206-8

5. Hawkey CJ, Talley NJ, Yeomans ND, et al. Improvements

with esomeprazole in upper gastrointestinal symptoms in patients taking

non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs including selective COX-2 inhibitors

(NASA1 — SPACE1). Am J Gastroenterol 2005,100(5):1028-1036.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1572-0241.2005.41465.x

6. Yeomans N, Lanas A, Labenz J, van Zanten SV, van Rensburg C, Racz I,

Tchernev K, Karamanolis D, Roda E, Hawkey C, Naucler E,

Svedberg LE. Efficacy

of esomeprazole (20 mg once daily) for reducing the risk of

gastroduodenal ulcers associated with continuous use of low-dose

aspirin. Am J Gastroenterol. 2008,103(10):2465-2473. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1572-0241.2008.01995.x

Relevant grants total over £2m, from Astra, Astra Zeneca, Merck

Sharpe & Dohme, MRC ROPA, Novartis and University of Dundee/EMEA (via

unrestricted grant from Pfizer). All awarded to CJ Hawkey for work between

1993 and 2013 for research on NSAID complications and their prevention,

including co-prescription of NSAIDs and PPIs.

Details of the impact

Our research has had an impact in six main areas: patient safety, quality

of life, healthcare costs, management guidelines, prescribing practice and

opportunities for the pharmaceutical industry.

Patient safety:

Before our research, the only way to reduce the risk of a non-steroidal

anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID)-associated ulcer complication was to avoid

using NSAIDs or to use low doses. Previously recommended measures such as

the use of slow release or effervescent preparations or enteric coating

were at best ineffective. NSAIDs were regarded as the biggest iatrogenic

cause of hospitalisation and death worldwide. The most conservative

estimates (UK) were that 1 in every 250-370 people being treated with

NSAIDs would be hospitalised for ulcer complications each year

[Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf, 2001;10:13-19]. With at least a 10% death

rate, this resulted in an estimated societal burden of 3,500-4,000

admissions and 400-1,000 deaths per annum. Estimates from other societies

and meta-analyses of clinical trials suggested greater harm, with annual

ulcer complication rates of 1 in 67 users, with two estimates of death

rates in the USA of 7,000-10,000 [Clin Ther 2010;32:667-677] and 16,500

[Gastroenterol, 1985;96,647-655].

Based on a Health Technology Appraisal (HTA) meta-analysis drawing on our

work [HTA 2006, 10(38); Am J Gastroenterol 2006,101:701-710] and studies

by others with other proton pump inhibitors (PPIs), the NICE

Osteoarthritis Development Group reported in 2009 that use of PPIs in

patients aged 55 or over reduced the risk of hospitalisation for

gastrointestinal bleeding by 54% and symptomatic ulcer by 63%, and was the

most cost effective prophylactic strategya,b. A pro rata

reduction in death could prevent between 216 and 540 deaths per annum in

the UK, with higher values if estimates from other countries are used.

Worldwide, NSAID use is extensive [PLoS Med 2013;10(2):e1001388]. Using

even the most conservative estimate above (1 hospitalisation per 370 users

per annum), several hundred thousand life-threatening ulcer complications

could be prevented annually, worldwide, by use of proton pump inhibitors.

Quality of Life:

As well as preventing ulcer complications, PPIs improve quality of life

by reducing dyspepsia and allowing continuation of treatment that would

otherwise be stopped. NICE estimate dyspepsia rates between 5.4% and 9.6%

per annum in NSAID users and a 57% reduction with PPI co-prescriptiona,b.

Another meta analysis reported higher rates (13.5%-31%) with the 66%

reduction by PPIs being identified as the most effective available

treatment or preventative measure for NSAID dyspepsia [Am J Med;

2006:119(5):448.e27-36]. NICE estimate that the combined effect of reduced

mortality and improved quality of life results in a gain of 5-10 QALYs

(quality adjusted life years) per thousand people treateda,b.

[QALYs are a measure of disease burden used to assess the value of a

medical intervention. They are based on the number and quality of years of

life that would be added by the intervention. One QALY is one year spent

in perfect health.]

Healthcare costs:

NICE report that the ability of PPIs to prevent hospitalisation and other

adverse events reduces healthcare costs to the extent that their use

`increases the estimated gain in quality adjusted life years at little or

no additional cost" with "savings from not having to treat adverse

effects'.a

Guidelines:

These observations led NICE to recommend that PPIs are considered for use

in all patients taking NSAIDsa. All other major guidelines

produced or updated in the past five years (Osteoarthritis Research

Society International [OARSI] 2008c, Cardiology 2008d,

American Colleges of Gastroenterology 2009e, and Rheumatology

2012f, place the PPI co-prescription strategy that we developed

at the heart of their guidelines, particularly for patients at increased

risk of ulcer complications. An updated Cochrane analysisg

supports the strategy, as do other national and international

recommendations.

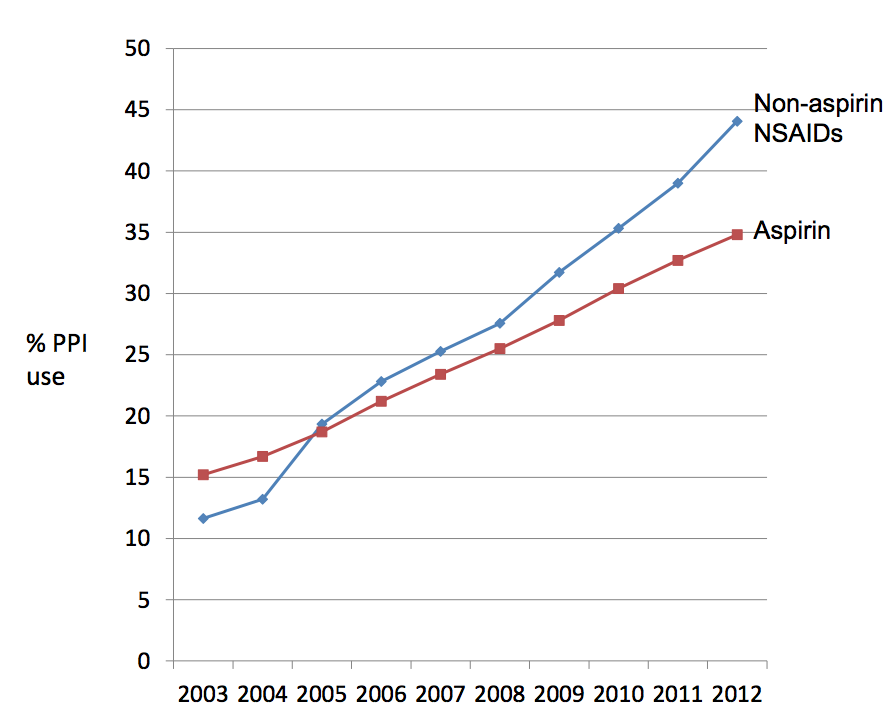

Prescribing practice:

To be effective, guidelines must be implemented.

Current data show progressive adoption of PPI co-prescription in UK (see

figure) and internationally [Am J Gastroenterol. 2008;103:1097-1103].

Clinical Practice Research Database Statisticsh show a rise in

co-prescription of a PPI in the UK from 27.6% in 2008 to 44.1% in 2012 in

patients aged >45 using non-aspirin NSAIDs, resulting in safer symptom

relief. During this time, aspirin use has doubled in the UK with a

concurrent rise in the proportion of patients receiving PPI protectionh

from 25.5% in 2008 to 34.8% in 2012, allowing patients to access the

cardiovascular and anti-cancer benefits of aspirin more safely.

Figure: Rates of UK co-prescription of PPIs in patients using NSAIDs and aspirin by year, based on data routinely collected from general practices with electronic systems that feed into the Clinical Practice Research Database.

Figure: Rates of UK co-prescription of PPIs in patients using NSAIDs and aspirin by year, based on data routinely collected from general practices with electronic systems that feed into the Clinical Practice Research Database.

Commercial Opportunities:

Esomeprazole is one of AstraZeneca's 10 leading medicines by sales.

Worldwide sales of this drug generated £3.9 billioni in revenue

for AstraZeneca in 2012, with an increasingly significant contribution

from NSAID ulcer prophylaxis. The effectiveness of PPI prescription has

also led to development of combination preparations, of which several have

so far been approved and launched internationally (Axorid: ketoprofen +

omeprazole 2009, Vimovo: naproxen + esomeprazole 2010, and Axanum: Aspirin

+ esomeprazole:2011)j.

Sources to corroborate the impact

a) Latimer N. Lord J. Grant RL. et al. National Institute for Health and

Clinical Excellence Osteoarthritis Guideline Development Group. Cost

effectiveness of COX 2 selective inhibitors and traditional NSAIDs alone

or in combination with a proton pump inhibitor for people with

osteoarthritis. BMJ. 339:b2538, 2009 http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/bmj.b2538

b) National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence. Osteoarthritis:

The care and management of osteoarthritis in adults. http://www.nice.org.uk/nicemedia/pdf/CG59NICEguideline.pdf

c) Zhang W, Moskowitz RW, Nuki G, et al. OARSI Recommendations for the

Management of Hip and Knee Osteoarthritis, Part II: OARSI evidence-based,

expert consensus guidelines. Osteoarthritis & Cartilage 2008; 16:

137-162.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016%2Fj.joca.2007.12.013

d) American College of Cardiology Expert Consensus Document on Reducing

the GI risks of Antiplatelet Therapy and NSAID Use 2008:

http://cardiocompass.cardiosource.org/cc2/openCont2?objID=108

e) Lanza FL, Chan FKL, Quigley EMM and the Practice Parameters Committee

of the American College of Gastroenterology. Guidelines for prevention of

NSAID-related Ulcer Complications. Am J Gastroenterol 2009; 104: 728-738.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1038%2Fajg.2009.115

f) Hochberg MC, Altman RD, April T, et al, American College of

Rheumatology 2012 Recommendations for the use of Nonpharmacologic and

Pharmacologic Therapies in Osteoarthritis of the Hand, Hip and Knee.

Arthritis Care & Research 2012; 64(4): 465-474.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1002%2Facr.21596

g) Rostom A. Dube C. Wells G. et al. Prevention

of NSAID-induced gastroduodenal ulcers. Cochrane Database of

Systematic Reviews http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD002296

h) Scrutiny of CPRD database. Corroborated by Dr Yana Vinogradova (pdf

available on request).

i) AstraZeneca 2012 annual report: http://www.astrazeneca-

annualreports.com/2012/documents/eng_download_centre/annual_report.pdf

j) Vimovo: http://www.medicines.ie/medicine/14981/SPC/VIMOVO+500+mg+20+mg+modified-release+tablets/#ORIGINAL