HEAL03 - Promotion and support of breastfeeding for new-born infants

Submitting Institution

University of YorkUnit of Assessment

Public Health, Health Services and Primary CareSummary Impact Type

SocietalResearch Subject Area(s)

Medical and Health Sciences: Nursing, Paediatrics and Reproductive Medicine, Public Health and Health Services

Summary of the impact

Our research, which identified effective and cost-effective interventions

to help women, particularly those in low income groups, make informed

choices and establish and maintain breastfeeding for newborn infants, has

changed health policy and practice nationally and internationally. The

findings have been included in national and international practice

recommendations including National Institute for Health and Care

Excellence guidelines. Active dissemination of our research outputs and

adoption of their recommendations have been associated with stepwise

increases in breastfeeding rates in the UK, particularly for socially

disadvantaged women who typically have low breastfeeding rates, and is

likely to be associated with improved health of infants.

Underpinning research

Breastfeeding improves important outcomes for mothers and infants.

Initiation and maintenance of breastfeeding in the UK have historically

been low, particularly in socially disadvantaged young women.

Breastfeeding is particularly important for the 10% of infants born

preterm or with low birth weight (LBW). York researchers conducted seminal

systematic reviews which identified effective and cost-effective

interventions to increase rates of initiation and maintenance of

breastfeeding.

(i) Initiation of breastfeeding: Our systematic review of 59

studies evaluating a range of policy, supportive and educational

interventions showed the effectiveness of multi-faceted packages of

interventions including: targeted, small group, interactive education

programmes and peer support for women with low incomes (1). Our Cochrane

review of randomised controlled trials (RCTs) identified the substantial

benefits of interactive health education interventions. For every 100

women receiving education, 20 extra initiated breastfeeding (2).

(ii) Maintenance of breastfeeding: Our Cochrane review of 34 RCTs

involving ~30000 mother-infant pairs in 14 countries showed that extra

support for women (particularly integrated lay and professional support)

increased the duration of breastfeeding. For every 100 women receiving

extra support, 5 more continued to breastfeed up to six months (3).

(iii) Breastfeeding infants in neonatal units: Our systematic

review of the effectiveness of interventions to promote breastfeeding or

feeding with expressed breast milk for infants admitted to neonatal units

(4) included 8 studies from 17 countries. We reported strong evidence for

the effectiveness of parent-baby "skin-to-skin" contact and UNICEF Baby

Friendly Initiative (BFI) accreditation. Our cost-effectiveness analysis

found that enhanced contact and support reduced overall costs and

increased "quality adjusted life years" for preterm or LBW infants,

especially those with very low birth weight (5). Our Cochrane review found

that feeding preterm or LBW infants in response to hunger and satiation

cues rather than a caregiver-led regimen shortened both transition to oral

feeding and hospital stay (6).

Researchers: Britton (Lecturer, Nov 1996 - present); Craig

(Research fellow, Nov 2004 - present); Dyson (Research fellow, Feb 2005 -

present); Lister-Sharp (Research fellow June 1996 - June 2002); McCormick

(Research fellow, Nov 2004 - Dec 2012); McFadden (Research fellow, Nov

2004 - Dec 2012); McGuire (Professor, Dec 2008 - present); O'Meara

(Research fellow, Nov 1995 - June 2013); Renfrew (Professor, Nov 2004 -

July 2012); Rice (Research fellow, Mar 2003 - present); Sowden (Senior

Researcher, Feb 1994 - present).

References to the research

1. Fairbank (Dyson) L, O'Meara S, Renfrew MJ, Woolridge M, Sowden AJ,

Lister-Sharp D. Systematic review to evaluate the effectiveness of

interventions to promote the uptake of breastfeeding. Health Technol

Assess 2000;4(25):1-171. DOI: 10.3310/hta4250

2. Dyson L, McCormick FM, Renfrew MJ. Interventions for promoting the

initiation of breastfeeding. Cochrane Database Syst Rev

2005;(2):CD001688. DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD001688

3. Britton C, McCormick FM, Renfrew MJ, Wade A, King SE. Support for

breastfeeding mothers. Cochrane Database Syst Rev

2007;(1):CD001141 DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD001141.pub3 [updated 2012]. DOI:

10.1002/14651858.CD001141.pub4

4. Renfrew MJ, Craig D, Dyson L, McCormick F, Rice S, King SE, et al.

Breastfeeding promotion for infants in neonatal units: a systematic review

and economic analysis. Health Technol Assess 2009;13(40):1-146.

DOI: 10.3310/hta13400

5. Rice SJ, Craig D, McCormick F, Renfrew MJ, Williams AF. Economic

evaluation of enhanced staff contact for the promotion of breastfeeding

for low birth weight infants. Int J Technol Assess Health Care

2010;26:133-40. DOI: 10.1017/S0266462310000115

6. McCormick FM, Tosh K, McGuire W. Ad libitum or demand/semi-demand

feeding versus scheduled interval feeding for preterm infants. Cochrane

Database Syst Rev 2010;(2):CD005255. DOI:

10.1002/14651858.CD005255.pub3.

This research was funded from the following competitive grants:

• Systematic review of factors which promote or inhibit the initiation of

breastfeeding. NHS R&D HTA programme. £56,000; 1998-9 (Lister-Sharp).

• Systematic review of interventions to promote the initiation of

breastfeeding. Canadian Child Health Field Bursary, Cochrane

Collaboration. £3304; 2002-3 (Dyson).

• NICE Public Health Collaborating Centre for Maternal and Child

Nutrition. £446,000; 2004-7 (Renfrew, Dyson).

• Infant feeding for babies in Special and Intensive Care Units. NIHR HTA

programme: £204,000; 2007-8 (Craig, Renfrew).

Details of the impact

Active dissemination of the research as a pathway to impact

We planned a targeted dissemination and implementation strategy to

promote the adoption of our research findings into practice in health

services across England. This included distribution of 60,000 copies of an

Effective Health Care bulletin (http://www.york.ac.uk/inst/crd/EHC/ehc62.pdf), which

summarised the findings of our systematic review of interventions to

promote the initiation of breastfeeding, to NHS practitioners and

service-users and supported this with a targeted media campaign. Second,

we produced a NICE `Evidence into Practice' briefing based on our

systematic reviews of interventions to promote breastfeeding. Finally we

conducted a national consultation with health professionals and

management, government, service user and voluntary organisations which

highlighted that the routine implementation of multifaceted, local

packages of breastfeeding services and the UNICEF UK BFI standards for

maternity services should be priorities for action (nice.org.uk/aboutnice/whoweare/aboutthehda/hdapublications/promotion_of_breastfeeding_initiati

on_and_duration_evidence_into_practice_briefing.jsp). Our

dissemination and implementation strategy has helped our research have a

significant impact on national and international health policy, clinical

guidelines, staff education, practice, and infant feeding behaviour as

outlined below.

Impact on policy statements, guidelines, toolkits and care pathways

Our work has directly contributed to the development of national and

international policy, including NICE Clinical Guidelines (CG) which UK

healthcare professionals are expected to follow.

--Initiation and maintenance of breastfeeding

- The NICE `Evidence into Practice' briefing which we produced was

referenced explicitly for its specific contribution to formulating

recommendations in the full NICE Clinical Guidance on postnatal care (in

2006 and updated in 2012) as well as being cited 16 times in the text.

This included the priority recommendation that all maternity care

providers in acute and primary settings should implement care using the

UNICEF UK BFI as a minimum standard (source 1).

- Our reviews and evidence summary documents were incorporated into the

NICE Maternal and Child Nutrition Public Health Guidance CG 037 (source

2) and the 2008 NICE CG on antenatal care (source 3). Both

NICE documents cited the reviews as evidence to support specific

recommendations for "interactive antenatal breastfeeding education" and

"one-to-one counselling and peer support", using the UK UNICEF BFI as a

minimum standard.

- The recent evidence document underpinning the 2013 revision of the UK

UNICEF BFI standards cited our reviews and evidence summary documents

more than 20 times (source 4).

- Our systematic reviews are cited in guidelines in Australia and the

USA:

- The Australian National Health & Medical Research Council

(NHMRC) Infant Feeding Guideline cites reference 3 in recommending

"evidence-based actions for promoting the initiation and duration of

exclusive breastfeeding" (source 5).

- The US Surgeon General's Call to Action to Support Breastfeeding

cites our research (refs 1 and 3) as the basis for recommending

"professional and lay support [.] to increase the duration of

breastfeeding", and for adoption of UNICEF-BFI training (source 6).

--Breastfeeding in neonatal units

- The systematic reviews of interventions to promote breast (milk)

feeding for infants in neonatal units (refs 4, 6) informed the

development of the NICE CG on donor breast milk banks (source 7),

the Department of Health toolkit for high-quality neonatal services (source

8), and the UNICEF-BFI guideline for neonatal units (source 9).

- The Australian NHMRC Infant Feeding Guideline cites ref 4 as providing

evidence that "expressed breast milk reduces the incidence of

necrotising enterocolitis" among preterm infants (source 5).

- WHO Guidelines on optimal feeding of LBW infants in low/middle-income

countries cites our review (ref 6) as evidence to recommend feeding

infants based on hunger cues (source 10).

Impact on education and training

Our work has had a direct influence on staff education and training. It

has formed the basis for the three modules on infant feeding of the

Department of Health-funded Royal College of Paediatrics and Child Health

e-learning programme on early years, freely available since 2009 to all

health professionals in the UK [www.rcpch.ac.uk/hcp].

Prof Renfrew worked closely with the charity "Best Beginnings" to produce

a DVD ('From Bump to Breastfeeding') www.bestbeginnings.org.uk/fbtb

which promotes and supports breastfeeding based on evidence from our

systematic reviews. 1.5million copies have been distributed free to

pregnant women throughout the UK since 2008.

Impact on behaviour and outcomes

-- Initiation of breastfeeding

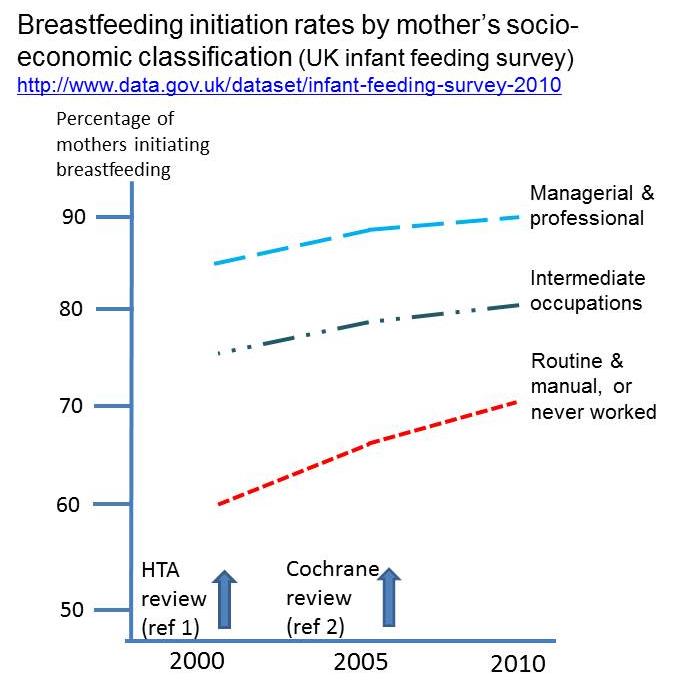

Data from the Infant Feeding Survey, collected every 5 years since 1990

and standardised for factors associated with breastfeeding (age, education

and social class), show that breastfeeding initiation remained static at

62% of all women in England & Wales between 1990 and 2000. Comparable

data in 2005 and 2010, however, show a 5% point increase at each time

point in the number of women starting to breastfeed since the start of the

York research programme, from 62% in 2000 to 72% in 2010 (source 11).

Standardised data are not available by socio-economic group, but non-

standardised data (see graph) indicate relatively larger and sustained

increases in the proportion of women from lower socio economic groups

starting to breastfeed in England & Wales from 2000 to 2010. This is

consistent with York's research (source 11). Changes in the

definitions used to categorize "socio-economic status" limit the direct

comparability of data from the IFS prior to 2000. However, no increases in

breastfeeding initiation rates were observed between 1995 and 2000 for

both "non-manual" (81%) and "manual" occupation households (61% ) before

this research was carried out.

-- Maintenance of breastfeeding

The 2010 UK Infant Feeding Survey found that the proportion of women

maintaining breast-feeding has continually increased from 2005. The

prevalence of breastfeeding at six weeks was static at 45% between 1995

and 2000, but then rose to 48% in 2005 and 55% in 2010. Six months rates

were 21% in both 1995 and 2000, but then rose to 25% in 2005 and 34% in

2010. Exclusive breast-feeding rates have also increased (at three months

they were 17% in 2010 compared with 13% in 2005, and at four months they

were 12% in 2010 compared with 7% in 2005). Rates of increase were highest

in low income women, reflecting our research recommendations to focus on

those where the potential to impact on important health outcomes is

greatest (source 11).

-- Health outcomes

Increased rates of breastfeeding, particularly amongst those at higher

risk improves health outcomes in infants in the short and long term. The

UNICEF report, Preventing

Disease and Saving Resources, estimates that even

moderate increases in breastfeeding could see millions in potential annual

savings to the NHS from improved health outcomes (source 12).

--Breastfeeding in neonatal units

In 2010, as part of the DH-funded regional Health Innovation and

Education Cluster (HIEC), York developed educational packages to support

quality-improvement initiatives to promote bonding, attachment and

breastfeeding in neonatal units based on our research. Following

implementation of recommendations from our reviews, the prevalence of

skin-to-skin care in neonatal units across Yorkshire & the Humber

increased from 20% in 2010 to >40% in 2012 and receipt of breast milk

on discharge from 40% to 52% (source 13). This has resulted in all

UK units now collecting breast (milk) feeding outcomes within the UK

national routine audit systems and the RCPCH National Neonatal Audit

Programme. This national audit found that the proportion of very preterm

infants receiving any breast milk at discharge rose from 54% in 2011 to

58% in 2012, which will reduce mortality and morbidity associated with

diseases such as necrotising enterocolitis (source 14).

Sources to corroborate the impact

- Routine postnatal care of women and their babies. NICE guideline

(2006) www.nice.org.uk/CG037

- Maternal and child nutrition: NICE public health guidance 11 (2008) www.nice.org.uk/PH11

- Routine care for the healthy pregnant woman. NICE guideline 62 (2008).

www.nice.org.uk/CG062

- Entwistle FM (2013) The evidence and rationale for the UNICEF UK

Baby Friendly Initiative standards. UNICEF UK.

- Infant Feeding Guidelines. National Health and Medical Research

Council (2012). www.nhmrc.gov.au/guidelines/publications/n56

- US Department of Health and Human Services. The Surgeon General's Call

to Action to Support Breastfeeding. Department of Health and Human

Services, Office of the Surgeon General (2011).

- Donor breast milk banks. NICE clinical guideline 93 (2010). www.nice.org.uk/CG093

- Department of Health. Commissioning local breastfeeding support

services (2009). http://webarchive.nationalarchives.gov.uk/20130107105354/http://www.dh.gov.uk/prod_consum_dh/groups/dh_digitalassets/documents/digitalasset/dh_106497.pdf

- Nyqvist KH et al. Expansion of the Baby-Friendly Hospital Initiative

ten steps to successful breast-feeding into neonatal intensive care:

expert group recommendations. J Hum Lact 2013;29:300-309. DOI:

10.1177/0890334413489775

- Guidelines on optimal feeding of low birth weight infants in low-and

middle-income countries. World Health Organization (2011). Available

from: www.who.int/maternal_child_adolescent/documents/infant_feeding_low_bw/en/

- McAndrew F, et al. Infant Feeding Survey 2010 www.esds.ac.uk/doc/7281/mrdoc/pdf/7281_ifs-uk-2010_report.pdf

- Preventing disease and saving resources: the potential of increasing

breastfeeding in the UK unicef.org.uk/Documents/Baby_Friendly/Research/Preventing_disease_saving_resources.pdf

- Yorkshire & Humber HIEC. Turning best practice into common

practice. Final report (2013) yhhiec.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2013/07/12120503_HIEC_Report_2012_2013_PRINT-FINAL.pdf

- National Neonatal Audit Programme, Annual Report 2012. www.rcpch.ac.uk/system/files/protected/page/RCPCH_NNAP_Report%202012%20(2).pdf