Changing Policy And Practice In The Prevention Of Suicide And Self-Harm

Submitting Institution

University of StirlingUnit of Assessment

Psychology, Psychiatry and NeuroscienceSummary Impact Type

HealthResearch Subject Area(s)

Medical and Health Sciences: Clinical Sciences, Public Health and Health Services

Psychology and Cognitive Sciences: Psychology

Summary of the impact

Our research has made an outstanding contribution to the policy and

practice of Health bodies acting to prevent suicide and self-harm.

Research conducted within the Suicidal Behaviour Research Laboratory

(SBRL) has systematically examined the causal antecedents of self-harm and

risk of suicide, leading to the creation of a new theoretical model of

suicide that: (1) has substantially informed new public policy, including

the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence's (NICE) and Royal

College of Psychiatrists' (RCP) Clinical Guidelines on the management of

self-harm and suicide risk, and; (2) has demonstrably altered practice,

both Nationally and Internationally, via the development of assessment

tools specifically designed to identify those who are at greatest risk of

psychological distress, self-harm and suicide.

Underpinning research

There is no doubt that suicide and self-harm (one of the most robust

predictors of suicide) are significant societal problems with substantial

personal and economic consequences — estimates suggest that each suicide

costs £1,290,000 (see goo.gl/z5AYgz).

Suicide is a large-scale problem, killing approx. 1 million people per

annum globally, leading suicide to be the leading cause of death

among young and mid-life people in some countries: for example, Scotland

has the highest rate of suicide in the UK, and rates of self-harm in the

UK are among the highest in Europe. Consequently, the prevention of

suicide and self-harm are key public policy priorities for most Western

governments, including all UK legislative bodies. Although there is

widespread agreement that action is required, it is equally clear that

suicide and self-harm are complex multi-cause problems that have proved

resistant to public intervention for many years. To date, no Government

has been able to demonstrate that their National suicide prevention

strategy has directly led to a reduction in suicide. Consequently, within

the public health arena there is now a consensus that, to maximise their

effectiveness, government policies must be informed by high-quality research evidence. Here we detail two key types of evidence from

the SBRL that have had clear and demonstrable Impact on Government policy

and practice Nationally and Internationally.

First, research in SBRL identified the scale of adolescent self-harm in

Scotland for the first time: we conducted the first, large-scale,

representative study of adolescent self-harm in the UK and identified the

key risk factors associated with adolescent self-harm1,2.

Second, and more broadly impacting on the UK and Internationally, over the

last 15 years we have been arguing that to better understand suicide risk

and, therefore, to prevent suicide, research needs to identify the

proximal mechanisms that translate distal risk factors into suicidal

behaviour. For example, take mood disorders, a distal risk factor:

although mood disorders are important correlates of suicidal behaviour

they are not sensitive enough to differentiate between the vast majority

of people with mood disorders who do not die by suicide and those who do

(<5% of those with depression).

In terms of psychological theory our research has moved beyond

psychiatric disorder explanations by identifying the psychological

mechanisms that make it more likely that, for example, one particular

individual with depression is at greater risk of attempting suicide than

someone else with depression. To accomplish this, we focused on

personality and cognitive risk factors, recently described in the new

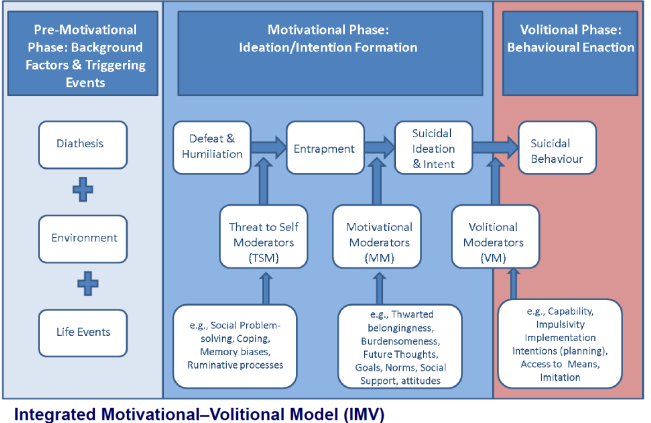

Integrated Motivational-Volitional model of suicidal behaviour (IMV; see

Figure 1 left-hand panel) and conceptual model of rural suicide3-6.

The IMV model provides a map of the proximal risk factors (e.g.,

perfectionism, rumination, defeat, entrapment) that explain when distal

risk will be translated into suicidal behaviour. Notably, our research

suggests perfectionism should be considered a key factor when assessing

risk of suicide7, because it increases one's sensitivity

to defeat and entrapment (the final pathway to suicide3,4).

Indeed, our findings highlight the need for policy and practice to

explicitly address how we equip young people (e.g., in schools) to manage

their expectations, and those of others, and we demonstrated the need to

ensure that perfectionism is included in risk assessment protocols. As a

result, attention to such factors is now included in key policy documents

and incorporated into risk assessment tools (cf. Section 4).

Over many years, we have conducted a programme of research to investigate

the causes of suicidal behaviour, developing new diagnostic assessment

tools, funded by a range of sources: between 2003 (when SBRL was

established) and 2013, our research to identify the proximal mechanisms of

suicide has been supported Nationally and Internationally (£3-4 million

from ESRC, MRC, NHS and UK and US Governments). The SBRL was led by Rory

O'Connor (developing from Senior Lecturer to Professor) between 2003 and

2013 at Stirling. Other personnel within Psychology have also contributed

to this programme of research, notably O'Carroll (2003-2013).

References to the research

1. O'Connor, R.C., Rasmussen, S., Miles, J., & Hawton, K.

(2009a). Self-harm in adolescents: self-report survey in schools in

Scotland. British Journal of Psychiatry, 194, 68-72. [Scopus

citation = 40; JCR IF 2011 = 6.606; 7/130 Psychiatry]

2. O'Connor, R.C., Rasmussen, S., & Hawton, K. (2009b).

Predicting deliberate self-harm in adolescents: a six month prospective

study. Suicide & Life-Threatening Behavior, 39, 364-375.

[Scopus citation = 12; JCR IF 2011 = 1.333; 45/125 Psychology,

Multidisciplinary]

3. O'Connor, R.C. (2011). Towards and Integrated

Motivational-Volitional Model of Suicidal Behaviour. In R.C. O'Connor, S.

Platt, & J. Gordon (Eds.). International Handbook of Suicide

Prevention: Research, Policy & Practice (pp.181-198).

Chichester: Wiley-Blackwell.

4. O'Connor, R.C., Rasmussen, S., & Hawton, K. (2012).

Distinguishing Adolescents Who Think About Self-harm From Those Who Engage

in Self-harm. B. J. of Psychiatry, 200, 330-335. [Scopus citation

= 3; JCR IF 2011 = 6.606; 7/130 Psychiatry]

5. Stark, C., Riordan, V., & O'Connor, R.C. (2011). A

conceptual model of suicide in rural areas. Rural and Remote Health,

11: 1622. [Scopus citation = 5; JCR IF 2011 = 0.979; 114/158 Public,

Envir. & Occupational Health]

6. O'Connor, R.C. & Noyce, R. (2008). Personality &

cognitive processes: Self-criticism, different types of rumination as

predictors of suicidal ideation. Beh.

Res. & Therapy, 46, 392-401. [Scopus citation = 20;

JCR IF 2011 = 3.295; 12/110 Psychology, Clinical]

7. O'Connor, R.C. (2007). The relations between perfectionism and

suicidality: A systematic review. Suicide and Life-Threatening

Behavior, 37, 698-714. [Scopus citation = 28; JCR IF 2011 = 1.333;

45/125 Psychology, Multidisciplinary]

Table 1. Funding awarded competitively via full peer review to

O'Connor as PI or Co-I

| Funding body — PIs |

Year |

Amount |

Title/Rating |

|

Chief

Scientist Office, Health Department — O’Connor (PI) with

Armitage (Uni. Sheffield), Smyth (Royal Infirmary of Edinburgh),

Beautrais (Uni. Auckland) & McDaid (LSE) |

2012-15 |

£224K |

A volitional helpsheet to reduce self-harm: A randomised trial. |

|

US Department

of Defense Basic Research Award — O’Connor (PI) with

O’Carroll (Uni. Stirling), D O’Connor (Uni. Leeds), Ferguson (Uni.

Nottingham) & Smyth (Royal Infirmary of Edinburgh) |

2012-15 |

$2.9 million

|

Study To Examine Psychological Processes in Suicidal ideation and

behavior (STEPPS). |

|

National

Institute of Health Research Programme

Grant — O’Connor

(Co-I) with Gunnell (Uni. Bristol), Kapur (Uni. Manchester)

& Hawton (Uni. Oxford) |

2012-17 |

£1.75 million |

A multi-centre prog. of clinical & public health research to

guide service priorities for preventing suicide in England. |

|

Northern

Ireland Government — O’Connor (PI) with Rasmussen (Uni

Strathclyde), Hawton (Uni Oxford) & Conachy (Uni. Belfast) |

2008-09 |

£79K |

Lifestyle and Coping Survey in Northern Ireland. |

| GL Assessment — O’Connor (PI) with S O'Connor, Carney & House

(NHS Ayrshire & Arran) & Ferguson (Uni. Nottingham) |

2008-10 |

£99K |

Development and Evaluation of the Paediatric Anxiety and

Depression Inventory. |

|

Chief

Scientist Office, Health Department — O’Connor (PI) with

Williams (Uni. Oxford), Masterton (Uni.

Edinburgh) & Smyth (RI of Edinburgh) |

2007-10 |

£224k |

The role of psychological factors in predicting short-term outcome

following suicidal

behaviour. |

|

NHS Scotland,

West of Scotland

Research Consortium — O’Connor (PI)

with Bradley (NHS Forth Valley) &

Rasmussen (Uni. Stirling). |

2006 |

£25K |

Understanding parasuicide from the suicidal person’s

perspective and a test of a

psychological model. |

|

Economic

& Social Research Council

Research Grant — O’Connor (PI) with

Masterton & MacHale (Royal Infirmary of

Edinburgh) |

2005-06 |

£46K |

Predictors of Suicidality:

Towards an Integrated

Motivational Model. |

| Choose

Life/Stirling Council Research

Grant – O’Connor (PI) |

2006-07 |

£7.5K |

A survey of young people's

experiences, beliefs and wellbeing

in Stirling. |

Details of the impact

The SBRL's research programme has had extensive National and

International reach. In this case study, we outline three distinct types

of Impact, on: (i) government policy, (ii) development of clinical

guidelines for the management of self-harm and suicide risk, and (iii)

using theory to inform practice in terms of the identification and

assessment of risk.

First, SBRL's research1,2,3,5 has

informed the development of National policy to prevent suicide and

self-harm. In Scotland, SBRL's research1,2 highlighted

the scale of adolescent self-harm in Scotland for the first time and the

key risk factors associated with self-harm and its repetitionA.

The former, a large study of a representative sample of 15-16 years

(N>2,000), was the most comprehensive study of its kind ever to be

conducted in Scotland. In Northern Ireland, in addition to O'Connor being

asked to address the Northern Irish Government's 2007 Inquiry into the

Prevention of Suicide & Self-harm, SBRL's research on rumination and

entrapment (key components of O'Connor's Integrated

Motivational-Volitional model of suicide4) was cited by

others in evidence to the Inquiry including the submission by the

Methodist Church in IrelandB.

In terms of having a direct impact on Government Policy on suicide and

self-harm, SBRL's research1,2,3,5 has informed

development of policy in Scotland & Northern Ireland by highlighting

the scale of self-harm, as well as identifying key risk factors and high

risk groups. Importantly, SBRL's research is cited in all the key policy

documentsC,D,E. Indeed, one of the specific objectives

(SO1) in the Scottish Government's Responding to Self-harm in Scotland

ReportC highlights training in schools, this was a key

recommendation from SBRL's research1,2. More recently,

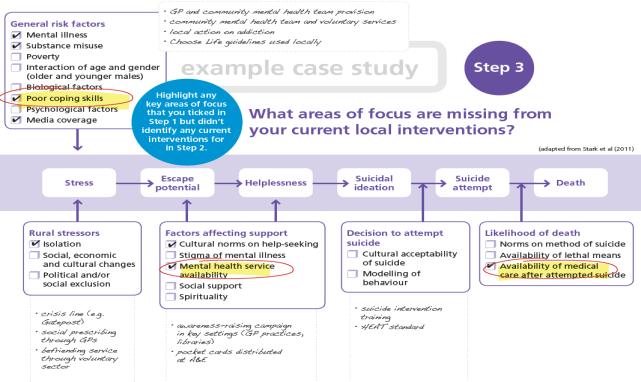

the Scottish Government has launched a national guide to help NHS and

Councils reduce risk of suicide among people living in rural areas (Fig 1

shows correspondence between model and tool). This guide and toolkitF

would not have been possible without our research and that of our

collaborators3,5.

Figure 1. O'Connor's IMV model (left) and a page from Choose Life tool

based on the model (right)

Figure 1. O'Connor's IMV model (left) and a page from Choose Life tool

based on the model (right)

Similarly, one of the recommendations in the Northern Ireland Suicide

Prevention strategy reviewE (Section A. Population

Approach. Action Area: Children & Young People) is to promote positive

mental health and emotional literacy in schools. This includes citation of

SBRL's research1,2. Our research is routinely employed

by Non-Governmental Organisations, e.g., Scottish Association of Mental

Health's submission to United Nation's Office of the High Commissioner for

Human Rights' Committee on Economic, Social & Cultural RightsG

cited our work on adolescent self-harm1,2.

Second, SBRL's research has informed the development of the key National

Clinical Guidelines on the management of self-harm, including the National

Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) guidelines for the

longer-term management of self-harm (2011)H. The NICE

guidelines are the gold standard recommendations for clinical care

throughout the NHS, and in all local authorities. Moreover, NICE

guidelines are recognised Internationally as a model of research-informed

clinical excellence, raising standards worldwide. Within the UK all

professional and care workers engaging with people who self-harm should

adhere to these guidelines because they describe the optimal clinical care

based on the best quality International research evidence. Our research1,2,3

on the prevalence of self-harm and the associated risk factors, causes and

motives for self-harm is cited within the NICE guidelines, as well as in

the Royal College of Psychiatrists' clinical guidelines on "Self-harm,

suicide and risk: helping people who self-harm" (2011)I.

Third, our research has informed practice, notably by informing advances

in the identification and assessment of suicide risk. For example, the

Suicide Assessment and Treatment Pathway guidelines (2009) developed in

ScotlandJ highlight perfectionism as a key risk factor,

citing our research7 as the sole evidence. The pathway

guidelines assist staff within the NHS, local authorities and the third

sector in the assessment of people at risk of suicide, and to provide

appropriate and timely treatment. Our work1,2 is also

included in the training of psychiatrists who are at the frontline of

suicide prevention efforts (goo.gl/NKU28t).

This work1,2 is also used by social enterprises; for

example, HarmLESS Psychotherapy (goo.gl/UrVTwE),

which was set up in 2010 to raise awareness about the issues which affect

people who self-harm cite our research. Importantly, our research has

International reach, as evidenced by US Defence agency funding (cf. Table

1). Equally, a US University has developed a range of diversity-specific

resources as part of a suicide prevention initiative, again highlighting

the role of perfectionismK. Our IMV model has also been

adopted by Lifeline Australia (a national charity which provides access to

24 hour crisis support and suicide prevention services across Australia),

citing our research as a key influence on their Lifeline Service Model (goo.gl/BNcjMV). Our research also

informed the Samaritans' media and public education UK-wide campaign

targeted at mid-life men from disadvantaged backgroundsL.

Sources to corroborate the impact

The names and details of five contacts are provided — these individuals

can corroborate the impact. Additional evidence cited above includes:

A. Scottish Government Health & Sport Committee Official

Report, 2009: goo.gl/8CCxAk Scottish

Government Child & Adolescent Mental Health & Wellbeing Debate,

2010:

goo.gl/w8yPBL

Scottish Executive Question Time, Suicide (Young People), 2010: goo.gl/g0GKEQ

B. NI Executive Committee for Health, Social Services & Public

Safety. Official Report (Hansard). Inquiry into the Prevention of Suicide

& Self-harm. UK Government, 2007: goo.gl/Hwppde

C. Responding to Self-harm in Scotland Final Report. Mapping out

the next steps of activity in developing health improvement approaches.

Scottish Government, 2010: goo.gl/xwTP2w

D. Refreshing the National Strategy and Action Plan to Prevent

Suicide in Scotland. Report of the National Suicide Prevention Working

Group. Scottish Government, 2011: goo.gl/7Ax6Np

E. Review of the evidence base for Protect Life — A shared vision:

The Northern Ireland Suicide Prevention Strategy. NI Government, 2010: goo.gl/ZMPJRB

F. Scottish National guide on suicide prevention in rural areas,

2013: goo.gl/ZHM6fO

G. Scottish Association of Mental Health's submissions to the

United Nation's Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights, 2009: goo.gl/XVNMXD

H. National Institute of Health and Clinical Excellence. Clinical

Guidelines on the Longer-Term Management of Self-harm, 2011: goo.gl/DKtcpo

I. Royal College of Psychiatrists' Report `Self-harm, suicide and

risk: helping people who self-harm', 2011: goo.gl/2ePDG1

J. Suicide Assessment and Treatment Pathway. Supporting Guidance

developed jointly by Choose Life (Scottish National Suicide Prevention

Strategy), NHS Lanarkshire, North and South Lanarkshire Council: goo.gl/t5lBy3

K. Nova SouthEastern University Office of Suicide and Violence

Prevention, 2009: goo.gl/ZG9P8e

L. Samaritans Media Campaign, 2012: goo.gl/m0zkD4