Improvements in egg quality and hen welfare have enhanced productivity in the egg industry

Submitting Institution

University of GlasgowUnit of Assessment

Agriculture, Veterinary and Food ScienceSummary Impact Type

EnvironmentalResearch Subject Area(s)

Medical and Health Sciences: Clinical Sciences, Neurosciences, Paediatrics and Reproductive Medicine

Summary of the impact

Key findings of two University of Glasgow research programmes have

transformed the UK egglaying

industry, driving substantial improvements in productivity and bird

welfare. First, two of the

largest international poultry-breeding companies adopted an innovative new

tool for assessing

eggshell quality that was validated by University of Glasgow researchers.

This tool has improved

eggshell quality through selective breeding, with increased numbers of

undamaged saleable eggs

(saving approximately £10 million annually in the UK alone), as well as

enhancing the hatchability

of breeding stock eggs. Second, University of Glasgow research on the

long-term health and

welfare implications of infrared beak trimming influenced UK policy

debate, preventing a ban on

beak trimming (due to be enacted in 2011) that would have exposed 35

million laying hens to

potential pecking injury or death, as well as costing the industry an

estimated £4.82-£12.3 million

annually.

Underpinning research

The Institute of Biodiversity, Animal Health and Comparative Medicine at

the University of Glasgow

is one of the few UK institutes that contribute specialist research in

poultry science directly to the

poultry industry. This research is directed by Dr Maureen Bain (Lecturer,

1990-2006; Senior

Lecturer, 2007-present) and Dr Dorothy McKeegan (Senior Lecturer,

2005-present).

Validation of a novel measure of eggshell quality

Cracked and damaged eggs account for 8-10% of total global egg

production, which was 64

million metric tons (over 1000 trillion eggs) in 2012, resulting in

substantial economic loss. For the

UK alone, this could amount to a yearly loss of £53.6 million. Cracked

eggs also pose a risk to food

safety, and may adversely affect hatching, thus reducing chick output. For

decades, poultry-breeding

companies used laboratory-based measurements, such as shell-breaking

strength and

non-destructive deformation, in their selective breeding programmes to

improve eggshell quality.

Although such traits are heritable, none has been proven to influence the

rate of egg breakage that

occurs during routine handling.

During the late 1990s, a test was developed at Leuven University,

Belgium, to detect both cracked

eggs and those at risk of cracking. This test evaluates the acoustic

vibration response of an egg

when subjected to a non-destructive impact generated by a lightweight

hammer making contact as

the egg rotates around its long axis, providing a measure of the ability

of an egg to dampen

vibration (`dynamic stiffness' or Kdyn). However, for this text

to be useful to the poultry industry, the

heritability of Kdyn and its value for predicting egg breakage

during routine handling first required

demonstration. Between 2001 and 2004, as part of the European Union (EU)

project `Egg

Defence', Bain and her team collaborated with Dr Ian Dunn (Roslin

Institute, UK), researchers at

Leuven University and Lohmann Tierzucht GmBH (a primary breeder of

egg-laying hens). Two

studies investigating Kdyn were proposed and led by Bain and

Dunn.

The first study, conducted between 2002 and 2003, showed that Kdyn

has a moderately high

heritability (i.e. the trait will respond directly to genetic selection)

and correlates positively with

other eggshell quality measures, such as breaking strength and thickness

(which can only be

determined by destroying the egg).1 Bain measured the eggshell

quality data of 3,000 eggs from a

pedigree population provided by Lohmann Tierzucht, comprising 1,500

offspring derived from

mating 32 sire with 240 dams. Dunn conducted the statistical modelling and

calculated the

heritability and genetic correlation for Kdyn from Bain's data

and values provided by Lohmann

Tierzucht.

The follow-up study (March 2004) established that Kdyn can

identify `risky' eggs.2 A field study was

set up by Bain in collaboration with Scottish egg producer Glenrath Farms

Ltd., who provided full

access to their production unit and grading equipment. The statistical

analysis was performed by

the team at Roslin. Of 1,660 eggs measured before and after passing through

the collection and

grading equipment, those with higher Kdyn values were

significantly less likely to be cracked.

Therefore, University of Glasgow research played a key part in validating Kdyn

as a useful tool for

selecting hens with superior eggshell characteristics, and in demonstrating

that this measure

reflects susceptibility to cracking during routine handling.

Contribution statement from B. De Ketelaere and J. De Baerdemaeker,

Leuven University: "Our

group has performed quite extensive research into [Kdyn],

and collaborated with Dr. Maureen Bain

in order to gain more insight, not only into its relation to breakage in

practice, but also with respect

to its heritability. This research was published jointly with the group

of Maureen [Bain] taking the

lead. We believe that both aspects, for which credit goes to Maureen

[Bain], have triggered the

wide interest in the AET [Acoustic Egg Tester] by major poultry

companies worldwide."

Determining the consequences of beak trimming

Injury caused by bird-on-bird pecking affects laying hens in both

intensive (cage) and extensive

(barn and free-range) systems, and is a major welfare and economic issue.

Commercial egg

producers use beak trimming to minimise such damage, which can result in

the loss of breeding

stock and egg production. However, beak trimming can potentially cause

loss of normal beak

function (reduced ability to feed, drink and preen), and short-term or

chronic pain and debilitation.

Beak trimming was traditionally performed by hand, using a hot blade to

simultaneously cut and

cauterise the beak. In 2008, McKeegan characterised the physiological

response of birds to

infrared beak trimming. This procedure uses a high-intensity infrared

energy source, which is

localised, non-contact and can be automated. This research — jointly

commissioned by the

Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs (DEFRA) and the British

Egg Industry Council

(BEIC) — assessed the chronic sensory (i.e. welfare) consequences of

infrared beak trimming.3

Beak nerve function and anatomy were examined at a range of ages in both

trimmed and non-trimmed birds by: (i) recording the responses of single sensory nerve

fibres that provide sensation

in the lower beak and (ii) by detailed microscopic and X-ray measurements

of beaks. The results

suggested that infrared trimming does not cause chronic pain or other

adverse consequences for

sensory function, such as neuromas (pain and abnormal sensations generated

by bundles of

nerves). The beaks of birds across all age groups tested had full

sensation with no evidence of

pain or numbness, even in regrown beak tips. Examination of beak healing

showed nerve

regeneration and the presence of specialised touch receptors by 10 weeks

after infrared trimming.

This research provided evidence that infrared beak trimming represents a

refinement compared

with previous approaches and that the welfare cost of beak trimming (acute

pain and some on-going loss of sensation) might be outweighed by the benefits (reducing

suffering and mortality of

injured laying hens; fewer hens injured or lost from bird-on-bird

pecking).

References to the research

Grant funding

i. `Egg defence' (2001-2004) EU 6th Framework Programme Priority 5:

QLRT-2000-01606.

Partner Work package 1, 6, 7 and 9 (£94,875); total value of project €2.6

million.

ii. Chronic neurophysiological and anatomical changes associated with

infra-red beak treatment

(2008-2009) DEFRA — Science Directorate and British Egg Industry Council

(£39,167)

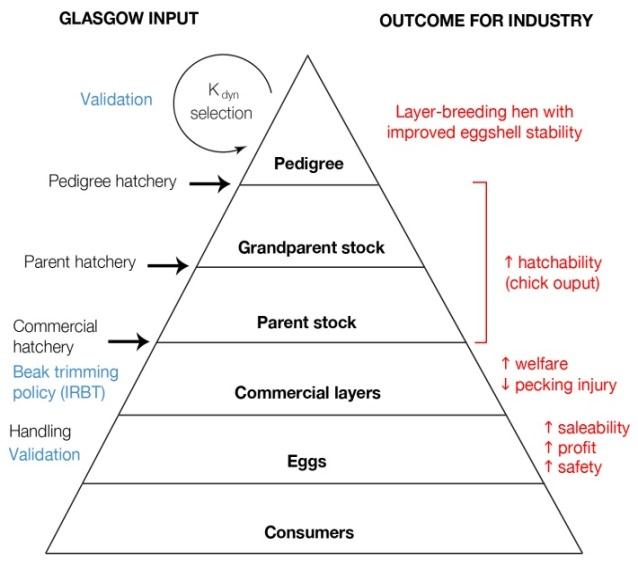

Details of the impact

There are approximately 35 million laying hens in the UK, which produced

9.3 billion eggs in 2012

with an estimated retail value of £957 million. The industry operates a

pyramid distribution (Figure

1) with the upper levels being the `layer-breeders', whose eggs are

fertilised and hatched. These

include pedigree birds selected for desirable characteristics, such as egg

dynamic stiffness (i.e. the

Kdyn metric tested by Bain). From these birds, the

great-grandparents and grandparents are bred to

create the parent stock, which are distributed around the world. It is the

progeny of these birds, the

commercial stock, that produce eggs for the table.

The combined research of Bain and

McKeegan has contributed substantially at

key levels within the layer industry

(highlighted in Figure), to improvements in

eggshell quality and hatchability and to

positive legislative change that affects the

welfare of UK commercial laying flocks.

These contributions have led to substantial

improvements in productivity, including

better eggshell quality, higher chick output

and decreased incidence of pecking

injuries, as described below.

Improving eggshell quality

As a result of Bain's validation of a novel

tool for assessing eggshell quality, several

international specialist layer poultry-breeding

companies are using the measurement of Kdyn in their breeding

programmes. These

include Lohmann Tierzucht GmBH,a a German-based breeder that

holds a 30% share of the world

laying market; and Hy-Line International,b a US-based breeder

that holds 45% of the world market

and 85% of the US market (the second largest egg-producing market in the

world). Since 2008,

both Lohmann Tierzucht and Hy-Line have tested all breeding selection

candidates for Kdyn in all

four of their pedigree lines for white and brown egg stocks,a,b

with Lohmann using the technology

on more than 20,000 pedigree birds annually. The process from selection of

pedigree birds using

Kdyn to commercial egg production takes approximately 3 years;

thus, table eggs with improved

stability have been available on the market since 2011.

To poultry companies such as Lohmann Tierzucht, the benefit of improved

egg quality is not only

relevant to commercial layers, but also benefits the breeding sector

because eggs with better shell

quality have improved `hatchability', leading to a higher chick output.a

Lohmann Tierzucht also

claim that "Eggs from birds with better DS [dynamic stiffness] achieve

a better revenue through

higher percentage of saleable eggs in relation to total eggs produced,"

citing 2% fewer egg

seconds depending on the age of the flock.a

Both companies have UK subsidiaries supplying substantial shares of the

UK market, with

Lohmann GB (36%) and Hy-Line UK (30%) accounting for 66% of all day old

chicks.a,b Both

companies use a single hatchery, Millennium Hatchery in Warwickshire,

owned by Hy-line UK. The

hatchery produces infrared beak-trimmed/vaccinated day-old chicks that are

transferred to rearing

farms for 16 weeks, after which they go into commercial layer

egg-production farms. Between

them, Lohmann GB and Hy-Line UK are responsible for some 22.4 million of

the 34 million laying

hens in the UK, all of which will have been selected for improved eggshell

quality on the basis of

the Kdyn measure, and which are capable of producing in excess

of 310 eggs per bird per annum

with an annual packer-to-producer value of approximately £500 million.

Therefore, the estimated

2% fewer egg seconds claimed by Lohmann incorporating Kdyn into

their selection programs will

have saved up to £10 million per annum to UK egg producers alone.

Influencing UK policy on welfare and productivity of commercial

laying flocks

Between 40% and 80% of the 35 million laying birds in the UK are subject

to injurious bird-on-bird

pecking, which can escalate to cannibalism, causing up to 20% mortality.c

To minimise this risk,

every hen hatched by Lohmann GB and Hy-Line UK, and intended for the

commercial production

of eggs with improved eggshell quality, has its beak trimmed using

infrared technology before

leaving the hatchery. Carefully managed breeding programs and investment

in improving eggshell

quality is intrinsically dependent on the welfare, and therefore

productivity, of layer hens. DEFRA

has estimated the economic benefit to the egg industry of birds not being

injured or killed (bird-on-bird)

could be anywhere between £4.82 and £12.3 million per annum.c

However, an EU directive (1999/74/EC) outlining the minimum standards for

keeping egg laying

hens had also prohibited all mutilation, and the UK enactment of this

legislation — including a ban

on beak trimming by any means — was due to be implemented on 1st

January 2011. In 2007, the

Farm Animal Welfare Council advised the government of the implications of

this ban, recognising

the greater welfare issue of pecking injury and the lack current UK

practice to prevent it if the ban

went ahead.d McKeegan's research, commissioned by DEFRA and the

BEIC in 2008, was

instrumental in the UK Government's decision not to go ahead with the ban

on beak trimming. The

findings were presented to DEFRA in March 2009,e and considered

by the Farm Animal Welfare

Council.f The findings were then summarised in a wider

consultation,g between January and April

2010, which was circulated to 79 poultry industry stakeholders, including

industry representative

bodies, animal welfare groups, veterinary associations, Government

agencies, academic institutes,

consumer groups and retailers.

The new draft regulations `Mutilations (Permitted Procedures) (England)

(Amendment) Regulations

2010' were presented to the Joint Committee for Statutory Instruments by

DEFRA in November

2010, together with an explanatory memorandum explaining the evidence

base, citing the Glasgow

research.h On 7th December 2010, the amendment was

debated by the First Delegated Legislation

Committee. Mr Plaice (Minister of State for DEFRA) stated: "the

researchers believe infrared was

the least painful method. I have said in my opening speech that we

accept that it does cause pain.

We do not believe that it causes chronic pain; the research at Glasgow

demonstrated that even if

neuromas are present, they are not functioning." The committee voted

to extend the use of routine

beak trimming of laying hens, but restricted the method used to the

infrared technique only.i

The new amendment came into force on 23 December 2010, preventing the

ban, which was due to

be implemented on 1st January 2011. Thus, McKeegan's research

has resulted not only in the

maintenance of improved welfare standards for laying birds, but also the

avoidance of what would

have been substantial economic losses for the industry had the ban gone

ahead.

Sources to corroborate the impact

a. Statements provided by Managing Director, Lohmann Tierzucht GmbH;

available on request.

b. Statements provided by Director of Research, Hy-Line International

Ltd; available on request.

c. DEFRA Impact

Assessment of an amendment to Regulations to allow beak trimming of

laying

hens by infra-red technology, January 2010 (para 8.6).

d. Opinion on

Beak Trimming of Laying Hens, Farm Animal Welfare Council, November

2007.

e. Commissioned research report to DEFRA: Chronic

neurophysiological and anatomical changes

associated with infra-red beak treatment, AW1139 (March 2009).

f. Farm Animal Welfare Council letter

to the Minister for Farming and the Environment (p.2, point

5).

g. DEFRA consultation

on an amendment to the Mutilations Regulations (permitted

procedures)

(England) 2007 (January 2010) Glasgow cited (Para 10.7.2).

h. Draft legislation laid before Parliament (Joint Committee on Statutory

Instruments): House

of

Commons and House

of Lords, both on 8 November 2010.

i. Debates and committee voting: House

of Commons (Delegated Legislation Committee), 7

December 2010; House

of Lords (Grand Committee), 8 December 2010.